The Life Well-Lived, part 1

Chapter 4 of The Techno-Humanist Manifesto

by Jason Crawford · September 27, 2024 · 11 min read

Previously: The Present Crisis; Fish in Water; The Surrender of the Gods, part 1 and part 2; Ode to Man.

The per-capita GDP of Canada has increased about thirty-fold over the last two centuries, from $1,441 in 1820 to $45,530 in 2022 (adjusted for inflation).1 This is an enormous increase. Are Canadians enormously better off?

That is, we’ve been assuming so far that material benefits improve human well-being. Do they? And if not, what’s the point of material progress?

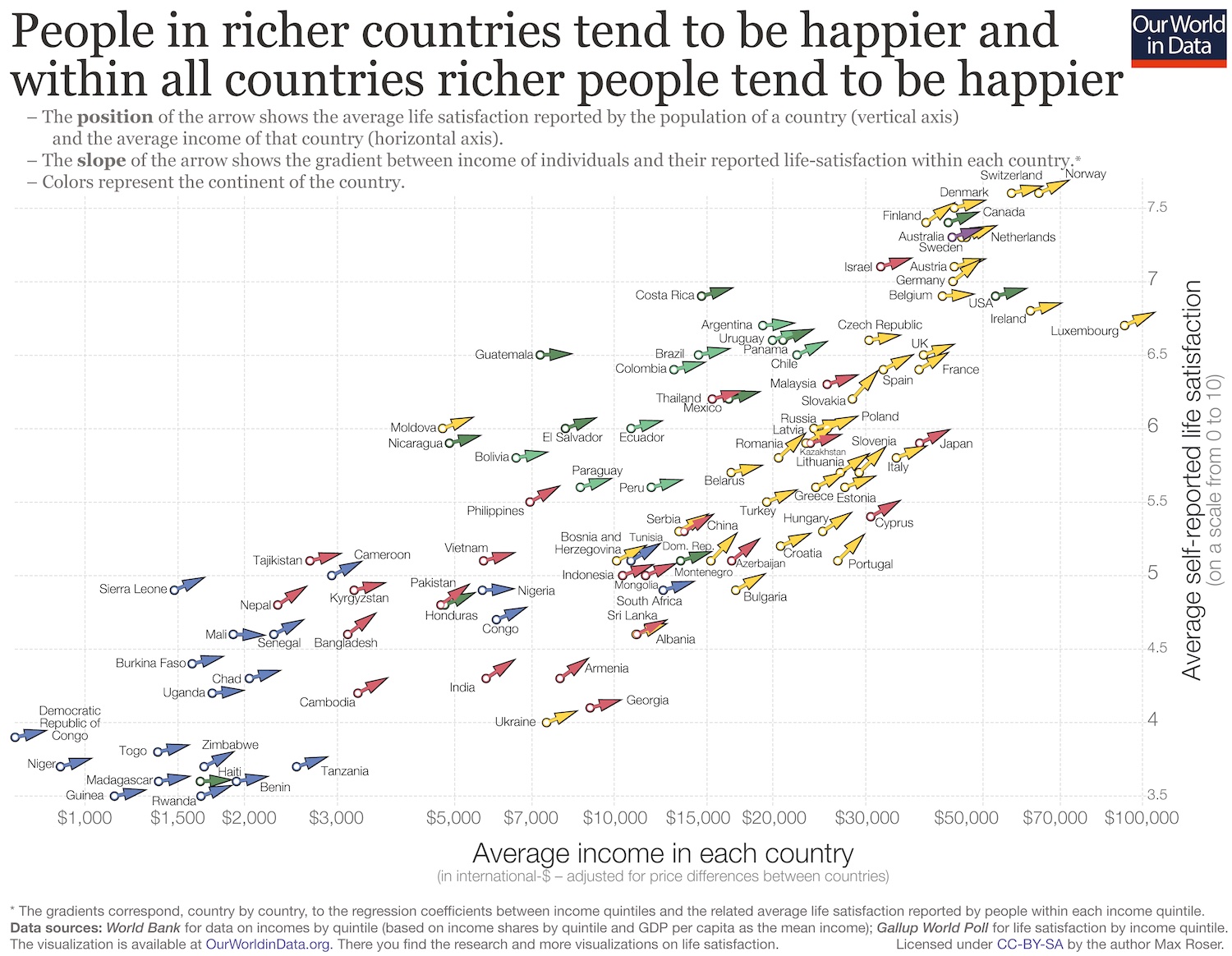

We might think, to start, that to measure well-being we could survey people about their happiness or life satisfaction.2 Psychologists and economists have been doing this kind of research for decades. At any point in time, happiness scores are positively correlated with income, both between and within countries: richer countries are happier, and within each country, richer people are happier:3

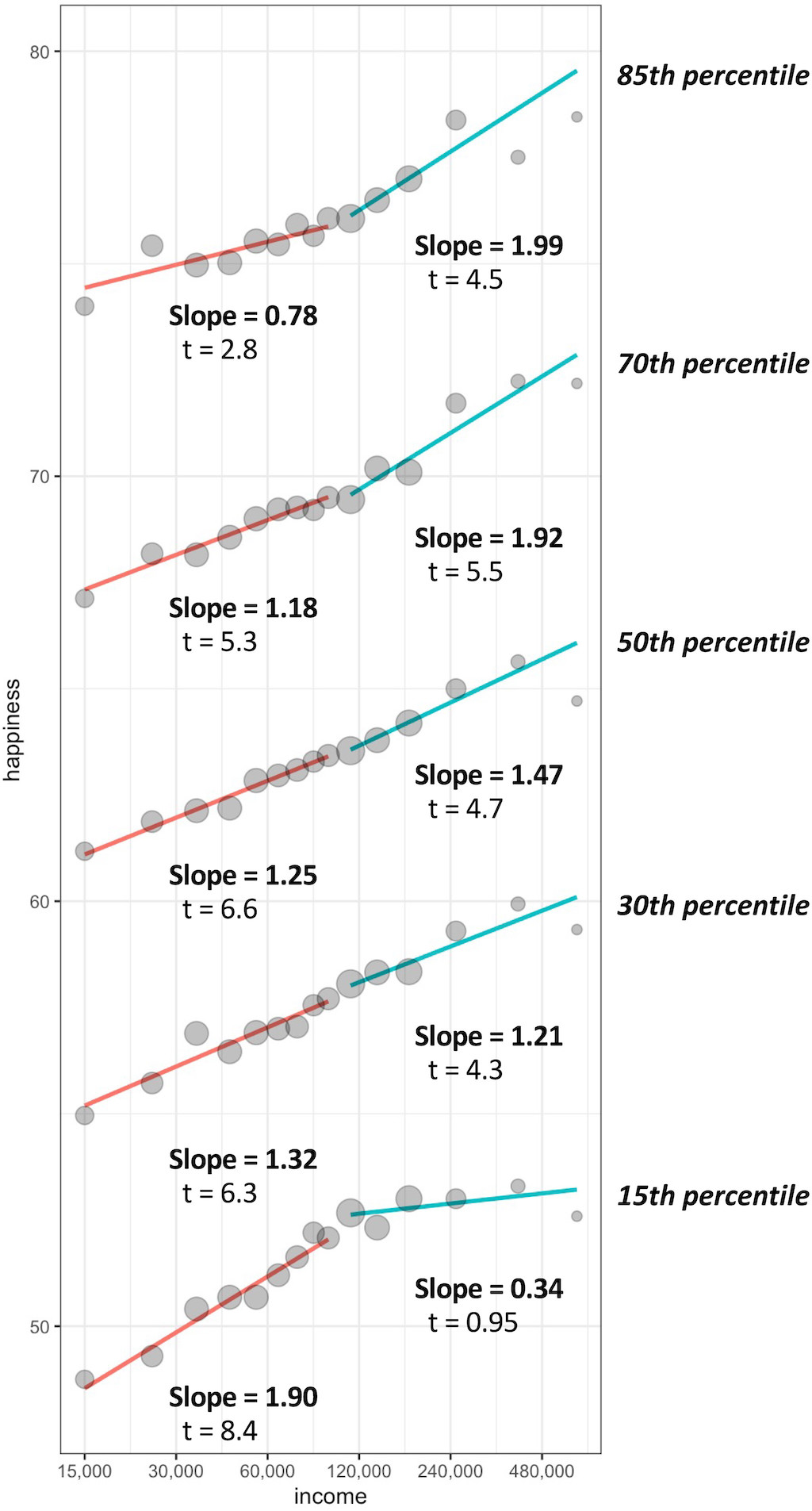

You may have heard that this effect levels off after a certain threshold of income—in the popular consciousness, around $75,000—and that beyond this, more money doesn’t make people happier. This was based on a study from 2010,4 but later research found that this was only true for the unhappiest people.5 That is, if you are deeply unhappy, more money past a certain point (somewhere between $60k and $90k, in 2010 dollars) won’t improve your happiness much. But most people continue to get happier with more income, with no limit that has been measured. In fact, the happiness of the happiest people seems to accelerate at higher levels of wealth:

Emotional well-being vs. income, for five different percentiles of the happiness distribution (Killingsworth 2023)

(Note that happiness scores are proportional to the logarithm of income; in the charts above, the x-axis is on a log scale. An intuitive way to understand this is that a 10% raise will make you equally happy no matter whether you are starting from a salary of $30k or $300k.)

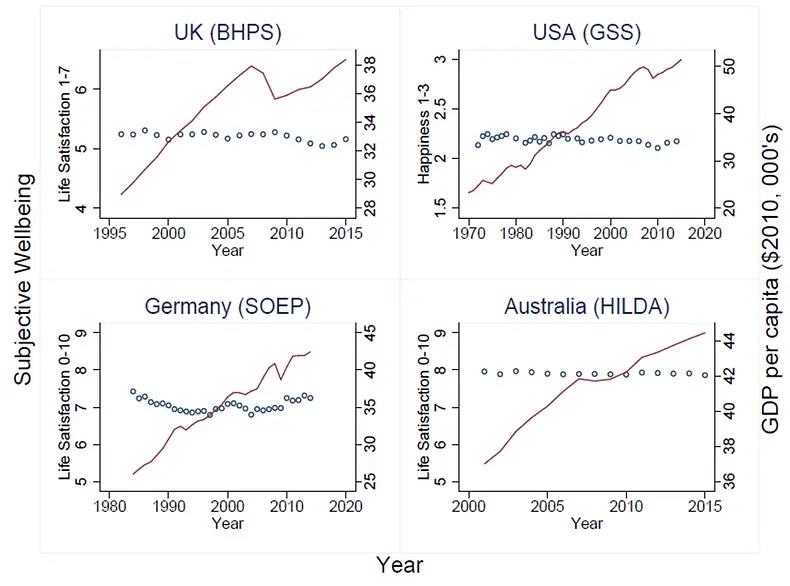

Comparisons over time, however, are muddier. While in many countries, happiness increases over time as the economy grows, in some it stays flat or decreases. Over the longest time spans we have data for, the correlation between economic growth and increases in happiness is weak to nonexistent. In the charts below for four wealthy countries, GDP per capita is plotted by the red line and keeps going up, while measures of subjective well-being are indicated by blue circles and are flat:6

Scholars continue to debate the right interpretation of this data,7 but for the sake of argument, let’s assume it’s true that economic growth doesn’t make people happier. Why would this be?

One explanation is that happiness is not absolute but relative. For one, it is relative to the recent past: someone with wealth and fame will still feel dejected when a beloved dog dies, and someone who is lonely and poor will still feel happy about landing even an entry-level job, despite the first person being more well-off than the second overall. In many cases, when people experience a major life event such as getting married, being laid off, or having a child, their mood resets after a time to the previous baseline, a phenomenon known as “hedonic adaptation.”8

Happiness is also relative to our expectations: if we expect to earn a bonus, or have plans to visit a good friend, and then it doesn’t happen, we’re disappointed, even though our objective situation hasn’t changed. In 1997, I had not yet graduated school or gotten married, and I was still living in my parents’ basement, but I felt that my life was going well—because I was 17. If that was still my situation today, in my mid-40s, I would no longer say that my life was going well. Expectations of growth and progress are built into our life assessments.

But some have interpreted this to mean that we are stuck on a “hedonic treadmill,” in which each advance becomes the new normal, taken for granted. The logical conclusion is that material progress can’t help the human condition. A report from the Happier Lives Institute states:

To put it bluntly, we are basically naked apes and have evolved to survive without needing many material belongings. As we’ve gone from having iPhone 5s to iPhone 6s, to iPhone 7s, to iPhone 8s and so on, these have not made a lasting improvement to our wellbeing because we just quickly get used to them. I know economists will find this conclusion almost heretical, but so much the worse for economics.9

My conclusion is the opposite: so much the worse for psychology, or more specifically, for making psychology the primary basis for our concept of human well-being.

A concept of well-being should be a guide—both in living our personal lives and in evaluating a society. It should indicate something substantive, and it should help us discover how to build well-being over time. Happiness, as understood in the research just discussed, is too subjective and relative for this purpose. What happiness surveys measure is closer to the first derivative of well-being than to its absolute level, telling us only the direction and magnitude of recent changes. If we take these surveys as our measure of value, then not only would we have to conclude that having better iPhones doesn’t matter to a society, but also that getting married, being laid off, or having a child doesn’t matter to an individual.10 Counterintuitively, happiness is not a good metric of human well-being.11

A better guide to well-being and human progress is whether people can achieve their goals and fulfill their values.12 The good life is one of constantly discovering, pursuing, achieving, and maintaining values.

“Value” is a broad term; moral philosopher Valerie Tiberius says the concept can include “projects, activities, relationships, and ideals.”13 Values can range from specific, tangible goals, such as a new car, to abstract ones that are maintained over the long term, such as a marriage, or even qualities of character in ourselves such as honesty. Values are what motivate us and guide our choices over a lifetime.

The conception of well-being as value-fulfillment is solid enough to ground us in reality, but rich enough to point us towards a life that is about far more than simply staying fed, clothed, sheltered, and alive. Yes, we pursue health, longevity, and comfort—values which are directly provided by material progress. But we also seek meaning and personal fulfillment: a career that uses our talents and does good in the world; loving relationships with friends and family; the enjoyment of art and music; an understanding of our place in the universe. And we seek self-actualization: the full exercise of our skills and abilities, regardless of whether this is needed for any practical end.

That last is worth emphasizing, because of how clearly it refutes the concept of humans as primarily seeking ease and comfort. On the contrary, we get bored and restless with nothing to do. We seek challenge, adventure, knowledge, and play. When the needs of physical survival don’t provide enough of that, we invent it for ourselves: games and sports, travel, storytelling, math and science. We run races, climb mountains, compose ballads, and peer through telescopes—not for survival or comfort, but to be fully human and fully alive.

I saw this clearly after my daughter was born. If ease and comfort were the goal of life, then as an infant, she was already at the pinnacle, with nowhere left to go. She had servants to feed, clothe, and bathe her, to carry her from room to room, to soothe her to sleep, even to wipe her bottom; her slightest whim or discomfort was attended to quickly if she but made it known. But she wasn’t content with this: she wanted to explore, to satisfy her curiosity, to test and expand her powers. She was given bright, shiny toys and a clean, white mat to play on—but she wanted to crawl beyond the mat, to the strange, messy world of grown-up things: to touch the carpet and the curtains, to crawl behind and underneath the chair, to handle a grown-up cup, to pull clothes out of the drawer, to grab at hair and glasses and clothing, to eat the tag hanging underneath the sofa. She would climb over cushions, or up a foam-block incline, or up my chest, apparently for the fun of doing so; she was exhilarated by the experience of sitting upright, and later of standing. She was constantly seeking novel experiences and self-actualization.

Focusing on value-fulfillment, rather than on feelings or mood, grounds us in reality. Compared to emotion, values and their achievement are objective. They are not relative, but absolute: we can have more of them. And rather than being stuck on a treadmill, we can accumulate them without limit. Indeed, if there is one lesson to be learned from the relative nature of happiness, it is that a good life is one of growth, of constant achievement, of upward motion—a dynamic life, not a static one.

If well-being is value-fulfillment, then to improve our lives we need both to choose good values and to get them.

Technology and wealth, for all their benefits, cannot choose your values for you. They can help in this process by giving you information, but the final choice is yours. It’s up to you to define the meaning of your own life and to choose a set of values that are healthy and form a coherent whole. To guide these choices is not the job of technology, but of moral philosophy.

What technology and wealth can do is empower us to pursue the goals we have chosen. When we view material progress this way, it is something much grander than a generator of comfort and leisure: it is the great liberator allowing us to pursue rich, full lives.

First, we have the chance to actually live those lives. Historically, only about half of newborn babies would even get to enjoy a full childhood, let alone adult life.14 As late as 1851, in England and Wales, a newborn had only about a two-thirds chance to make it to adulthood, and less than 40% to live to age 60. Today, over 95% of those newborns will live to age 60.15 Even having a full adult life was once a lucky break; now it’s practically a birthright.

And more of that life can be devoted to the things we enjoy most—recreation, loved ones, personal enrichment, self-actualization—because less and less of it is devoted to basic necessities. At the start of the 20th century, the average American household devoted the vast majority of its expenditure, about 80%, just to food, clothing, and housing; by the end of the century, that was down to 50%.16 More wealth doesn’t just mean more of the same stuff, and it doesn’t even just mean more luxurious versions of the same stuff: it means that once you have fed, clothed, and housed yourself, you still have money left for dancing lessons, camping gear, a family photo session, or a trip to Taipei.

At the same time that incomes have been rising, working hours have been falling, from 60–70 hours a week in 1870 to 35–40 by 2000.17 In other words, as real wages increase, we “consume” part of that income in the form of increased leisure. This is getting time back for ourselves to spend on what we care about most, and time saved is life gained.18 Not only have working hours decreased, the work week is shorter (a two-day weekend is now standard), and we get more vacations and holidays as well (four weeks a year in the US, up from one week a year in 1900).19

And the greatest gains in leisure have gone to those who need it most: the old, and the young. The old now get to enjoy retirement, which was unknown before the 20th century.20 The previous norm was to work until incapacity or death: in 1880, 78% of 65-year-old men were still working.21 Now most of those over 65 can devote full time to hobbies, travel, or grandchildren. And retirement has effectively gotten longer as life expectancy has increased: someone retiring at age 60 in 1920 could expect to enjoy fifteen more years; by 2013 another nine years had been added to that.22 Between this and the shorter work week, a 20-year-old man today can expect to spend only 23% of his remaining hours working, whereas in 1931 that was closer to 39% (and evidence suggests that it was even higher in the late 1800s).23 Increases in leisure have given us back a sixth or more of our lives.

As for children, they no longer have to work either—as they did through most of history, whether a bucolic life on farms or harder, more dangerous work in mines and early factories. And when children don’t have to work, they can go to school. One of the noblest consequences of material progress over the last few centuries is more education. As late as 1910 in the US, the high school graduation rate was only 9%; by 2012 it was 80%.24 Worldwide, literacy rates have increased from 12% in 1820 to over 87% today.25 A more educated mind is one more ready to take on engaging and high-paying work, to appreciate the accomplishments of culture, and to participate in civic society.

Consider also domestic life. The home was completely transformed in the 20th century by plumbing, gas, and electricity; by appliances such as the washing machine, vacuum cleaner, refrigerator, and dishwasher; and by consumer goods such as pre-made clothing and packaged foods.26 Before, keeping house was a full-time job: hauling buckets of water from the well, making every meal from scratch, sewing shirts and dresses. “Laundry day” was literally an entire day of the week. The 20th-century home didn’t just increase comfort: it helped to liberate women from their role in domestic service—whether the unmarried ones who left service jobs for higher-paying and more independent jobs in industry, or the housewives who did this work without pay and often without recognition.27 Women’s workforce participation increased from 23% in 1910 to 60% by the end of the century.28

Material progress doesn’t just give us luxury, comfort, and leisure. It moves us up a hierarchy of values, freeing up money, time and energy spent on the basics and letting us redistribute them towards the fulfillment of a richer life.

We have no way to directly measure human well-being. GDP does not measure it. Life expectancy, child mortality, energy consumption, even literacy rates do not measure it. It is not the same as having plumbing, electricity, motor transportation, or internet service. It is not equivalent to reductions in disease, pollution, or malnourishment. But all of these things empower us to achieve it. And when all of these measures are moving in the right direction, we can be confident that human well-being is, too.

Next: Chapter 4, part 2.

Parts of this essay were adapted from “Reflections on six months of fatherhood.”

For more about The Techno-Humanist Manifesto, including the table of contents, see the announcement. For full citations, see the bibliography.

-

These figures are given in international dollars at 2011 prices: “GDP Per Capita, 2022.” ↩

-

The difference between these terms is subtle, but in general “happiness” refers more to an emotion and “life satisfaction” more to a cognitive evaluation. Some papers combine the two without making much of a distinction, and I won’t be making a sharp distinction here. ↩

-

Ortiz-Ospina and Roser, “Happiness and Life Satisfaction.” ↩

-

Kahneman and Deaton, “High Income Improves Evaluation of Life.” ↩

-

Killingsworth et al, “Income and Emotional Well-being.” ↩

-

Our World in Data sides with Stevenson and Wolfers (2008) who claim that the paradox goes away with better analysis of data; Happier Lives Institute favors Easterlin and O’Connor (2022) who say that it remains if you look over long enough time periods. ↩

-

Ortiz-Ospina and Roser, “Happiness and Life Satisfaction.” ↩

-

Plant, “Faster Economic Growth.” ↩

-

Nozick’s thought experiment of “The Experience Machine”; the concept of “wireheading,” demonstrated in rats by Olds and Milner (“Positive Reinforcement by Electrical Stimulation”); the reductio ad absurdum proposed in “My friends who are parents.” ↩

-

Because of these limitations, the field of ethics debates a wide variety of theories of well-being, not just ones defined entirely by subjective experience. For a survey, see Eden Lin, “Well-Being, Part 2: Theories of Well-Being” in Philosophy Compass ↩

-

For an academic treatment of this concept, see Tiberius, Well-Being as Value Fulfillment. For an influential popular account, see Rand, The Virtue of Selfishness, particularly “The Objectivist Ethics.” ↩

-

Tiberius, Well-Being as Value Fulfillment, 11. Rand gives a concise definition: “‘Value’ is that which one acts to gain and/or keep” (Virtue of Selfishness, 15). ↩

-

Roser, “Mortality in the Past.” ↩

-

Ortiz-Ospina, “Life Expectancy.” ↩

-

Chao and Utgoff, “100 Years of US Consumer Spending Data.” ↩

-

Reportedly a maxim of English teacher and publisher Sir Isaac Pitman, and now the motto of Boom Supersonic. ↩

-

Gordon, Rise and Fall of American Growth, 500. ↩

-

Based on detailed longevity figures at every age from England & Wales: “Not Just Child Mortality.” Similar numbers hold for many other countries: “Life Expectancy of People of Different Ages.” ↩

-

These figures are from Nick Crafts, “The 15-hour Work Week.” An earlier, working draft of this paper (2021) gave estimates going back to 1881, at which point the figure was about 50%. However, this was based on data from Johnson (1994), which may have problems of interpretation and not be comparable to the data from 1931 on. ↩

-

Gordon, Rise and Fall, 284. ↩

-

Gordon, Rise and Fall, 71–76, 85–88, 113, 121–125. ↩

-

Schwarz, More Work for Mother, 22–23, 64, 165–167, 188–191. Note, a major theme of this book is that the liberation did not happen right away, nor was home technology the direct and sole cause. At first, the result was to increase standards of domestic cleanliness, without reducing the burden on housewives: “more work for mother.” But the new technological home was a catalyst for a social movement that eventually redefined women’s role in society. ↩