The Surrender of the Gods, part 1

Chapter 2 of The Techno-Humanist Manifesto

by Jason Crawford · July 23, 2024 · 15 min read

Previously: The Present Crisis, Fish in Water.

So far we have told the story of progress as one of humanity climbing out of poverty, isolation, disease and death into abundance, connectedness, health and safety. More fundamentally, it is a story of the expansion of human agency.

Our primitive ancestors lived at the mercy of nature. They ate what food they found: what edible plants happened to be growing nearby, what game they could catch. They fashioned tools, clothing, and shelter out of found materials: wood, stone, leaves and grass; the hide, hair, bones, or shells of animals. They might temper these materials with fire,1 but they could not fundamentally transform them. And as nomads, they were forced to limit their possessions to what could be carried. Until about ten thousand years ago, they did not even have draft animals; they controlled no power sources other than their own muscles.2

They had little choice of where to live: when local food resources ran out, they moved on—and they were constantly on the move. They had little choice of what to do with their lives, as any division of labor within the tribe was extremely limited—hunting, foraging, tool-making—and much of that determined by social roles.3 They had little choice of whom to socialize with: they were a part of the community they were born into.

When their environment changed, they had to simply react as best they could. They had little to no ability to predict the weather, or to grasp changes in climate. They had no techniques to prevent disease, not even washing hands or boiling water. They fell victim to attacks from wild animals and to raids from other tribes. We don’t have vital statistics from this era, but estimates of historical world population show very low growth rates for a very long time, which implies high mortality.4

Every aspect of their lives was dominated by chance factors in their environment. Although they lived as best they could; although they applied all their intelligence, effort, and will; and although they were surely no less clever and brave than you or I—the life they could create was still merely a tiny enclave carved out of a vast world.

The advent of agriculture and settled society over ten thousand years ago was a major leap forward in human agency. For the first time, we ate not the plants we found and the game we caught in the wild, but the crops we had sown and the livestock we had raised. We chose where to live and we made our homes, finally able to invest in them for the long term.

The first settlers and agriculturalists did not have much choice in these things, and their options were poor. They probably worked harder than hunter-gatherers, and they had smaller stature, indicating worse nutrition.5 Some have interpreted the shift to agriculture as a mistake, even “the worst mistake” in history.6 More likely, hunter-gatherers were led or forced into agriculture by circumstances beyond their control, such as rising population density or changes in climate.7 To call this evolution a “mistake” is ahistorical: a mistake implies a choice, but primitive peoples had no ability to direct the course of their societies, nor even to comprehend when a change of this magnitude was occurring. The lesson instead is the extremely limited agency of hunter-gatherer societies: even if they enjoyed their lifestyle, they were unable to keep it when the environment changed.

In any case, those who did choose to settle down laid the foundation for a much greater and more powerful civilization. With permanent settlements, we could accumulate possessions, including things too heavy to carry. Crucially, we could build large furnaces. And with them, we could generate the intense heat needed to transform materials: to smelt metals, to blow glass, to kiln clay and limestone. We had leapt beyond wood, stone, and other found materials, to create new materials that vastly expanded our options: metal afforded new types of tools, glass and ceramic new ways of storing food, cement and brick new methods of building.

We began to harness energy beyond our own muscle and channel it to our purposes: wind, water, animals. We guided and magnified it using gears, levers, pulleys, and screws. These afforded new ways to grind grain, saw wood, or lift stones and beams—whether to lighten our load, or to increase our strength.

With new materials and energy sources, we began to refashion the world we had found into a new and distinctly human world. We plowed fields, paved roads, dammed rivers. We built cities full of homes, shops, palaces, temples. We connected the continents via great ships that crossed oceans, effecting a global redistribution of crops, livestock, and people.

In this new world a much greater range of professions was open. While most workers still labored in the fields, some could specialize in the crafts: blacksmithing, weaving, pottery, carpentry. A few could become merchants or sailors, and travel the world. A very privileged few were even able to devote themselves to knowledge, law, art, or religion.

By this era, humanity had already far surpassed any other species; our command of nature was unmatched. And yet, by today’s standards, these people were still helpless.

Every human endeavor was vulnerable to random shocks and failures. Agriculture could fail due to drought, frost, blight, or pests. Even under the best circumstances, productivity was very low: about 1,000 kg of cereal-equivalents per worker per year, barely enough to feed the worker himself and his own family.8 With small surplus and little ability to reserve it for hard times or to transport it to the relief of stricken regions, famine was common.9

Manufacturing processes were variable and unpredictable. The iron-maker could not set his furnace to a precise temperature, because he didn’t have a thermometer, nor a concept of temperature that allowed for any precision. The ore he fed into that furnace contained impurities from nature, but he had no way of testing for them, nor the scientific knowledge to identify them. As late as the 1800s, blast-furnace managers were expected to have a feel for their furnaces and to run them by instinct.10 Finished products, from horseshoes to boilerplates, were fashioned by hand, between hammer and anvil or hand-operated rollers, and could have no more precision than hand and eye could coordinate.

Transportation of all forms was subject to the vagaries of the weather. Ships sailed by the grace of the wind, and could not move if it ceased to blow. The ability to navigate the open ocean was not widespread; most merchant voyages hugged the coast or plied a few known routes that followed seasonal monsoon winds.11 Travel on land was worse: slow, rough, and expensive; across a landscape filled with mountains, rivers, canyons, and other insuperable obstacles. Storms could cause shipwreck; rain could turn dirt roads to mud; snow could block a mountain pass for an entire winter.

Harnessing energy was also subject to chance. Windmills only turn when the wind blows. Water power was limited to river sites, and it would stop when the river ran low or froze over in winter. Neither can be stored, transported, or scaled up: they must be used when, where, and as they are found. For heating and lighting, too, we used found sources of energy: wood and coal, fats and oils, straw, brush, even animal dung—whatever was around that could burn. With little ability to purify our fuels, they gave off acrid smoke that damaged eyes and lungs.12

Disease was rampant. Epidemics were exacerbated by dense urban populations and by people living in close proximity to livestock. The control of disease was limited to very crude measures such as the quarantine and a few treatments such as cinchona bark for malaria. When plague struck, people turned to prayer and repentance. The sick did not even have the knowledge or ability to keep from infecting their own dearest loved ones.

It was still a world ruled by the gods, and humanity lived and died at their whim.

Helplessness was such a feature of the human condition that it was seen as the right and natural order of things. In 1722, when inoculation for smallpox (a forerunner of vaccination) was gaining popularity in the West, one London reverend preached vehemently against it. Disease, he argued, was sent by God—“either for the trial of our faith, or for the punishment of our sins.” In any case, it was God’s prerogative alone to send disease, and indeed to arrange even “the most minute circumstances of life”:

Shall we presume to rival him in any instance of providence, find fault with his administration, take the work out of his hands, and manage for ourselves? … Let the atheist then, and the scoffer, the heathen and unbeliever, disclaim a dependence upon providence, dispute the wisdom of God’s government, and deny obedience to his laws: let them inoculate, and be inoculated, whose hope is only in and for this life!13

This trust in the wisdom of divine providence extended even to natural disasters. When a great earthquake and tsunami struck Lisbon in 1755, killing tens of thousands and destroying much of the city, commenters bent over backwards to justify this atrocity and absolve their God. Some called it a punishment for the wicked lifestyle of the inhabitants of Lisbon. Protestants said it was targeted at Catholics for prosecuting the Inquisition. Rousseau even blamed the destruction on humans, for choosing to build tall buildings in dense urban centers.14

This fatalism was gradually eroded by Enlightenment rationality and material progress. We mitigated the destruction from earthquakes not by abandoning cities, but by studying seismology and structural engineering, and then designing earthquake-proof buildings. When disasters strike today, from pandemics to financial crises, we do not attribute them to Providence; we call them failures of policy and leadership. We no longer consider random events to be uncontrollable—we insist on controlling them.

And we have now achieved unprecedented levels of control over our world. Both agriculture and manufacturing are now consistent and reliable. With irrigation, we no longer depend on rain; with pesticides and herbicides, we fend off attacks from nature. With chemical assays and computerized machinery, we process raw inputs from any source, of any makeup, and produce pure, consistent alloys, their composition measured to hundredths of a percent.15 And we have created not only abundance, but incredible variety: our supermarkets are stocked with dozens of flavors of every product from cereal to pasta sauce; our shopping malls are a paradise of material goods to suit every individual need, style, and taste.

We have mastered the use of energy. The invention of the engine enabled us to convert fuel into motion, breaking our dependence on inconstant power sources such as wind and water. Energy usage became reliable and scalable; we could deploy it anytime, anywhere. With industrial chemistry, we purified the fuel itself, so it burned with less soot, ash, and smell; with electricity, we tame the very lightning.

Social life is no longer limited to the community you happened to be born into. If your hometown does not excite you, you can find a more suitable one, almost anywhere on Earth. If you wish to learn your art or craft from a master, you can find the world’s best teachers and sit at their feet, virtually or literally. If your local community shuns you, you can find a supportive community online. You can participate in almost any marketplace on the planet: for both buyers and sellers, this opens up a world of choices and opportunities.

We have radical agency over our information diet as well—even though that is a contrarian position today. In the past, people heard what news happened to reach them, often via gossip and hearsay; now we have instant access to all the information in the world. Despite algorithmic feeds and social media bubbles, we have much more ability than at any time in history to escape our provincial worldview and adopt a more cosmopolitan one. Before printed books and libraries, fact-checking was near impossible; before the Internet, it was often prohibitively difficult; now it is almost trivial. Few people exercise these abilities as much as they should—but that has always been the case, and those who do exercise them have an outsized influence on the world. Besides, if you think the average person today is misinformed, compare them to the sailor who feared monsters at sea, or the villager who joined in literal witch hunts.16

Our command of the material world results in greatly expanded choice in our individual lives. More than ever, we can choose what work to do, where to live and when to move elsewhere, whom to marry (if anyone) and when, how many children to have (if any) and when to have them, whom to associate and keep in touch with, what art and entertainment to experience, how to express ourselves in style and fashion.

Not everyone is happy with this new world of expanded choice. Some people feel adrift on a sea of options, and look wistfully to a bygone era when they would have been shepherded into traditional social roles. Some commentators worry that with the fading of those traditions, people are making choices that leave them personally unfulfilled or erode the social fabric, such as avoiding marriage and children.17 This much is true: with greater choice comes greater responsibility to make good choices. But if people make poor ones, it’s a mistake to blame that on the expansion of choice itself, or on the material advances that helped expand it, or on the scientists, inventors and industrialists who created those advances. Instead, we should challenge moralists, teachers and parents to provide better guidance for how to live a good life and create a good society in a world of greatly expanded choice.

Another result of material progress is a more secure and stable world. Our control of disease, for instance, has never been stronger. This may seem audacious to declare mere years after the worst pandemic in living memory. But consider: When the Black Plague struck in the 1300s, we did not even have the germ theory to understand what was happening, and mass death ensued. When an influenza/pneumonia epidemic hit the world in 1918, we had neither a vaccine for the flu nor antibiotics for the pneumonia. When covid arrived in 2020, the scientific community used genomic surveillance to track its history and its spread, tested hundreds of treatments in parallel, and developed a vaccine in record time based on novel mRNA technology.18 The Plague is estimated to have killed 30% or more of the population it swept through; the 1918 flu killed about 3%; covid about 0.3%.19

Human agency sometimes advances two steps forward and one step back. Technology grants capabilities but also creates new hazards. But these hazards, too, we learn to control—and we are far better at this today than in the past.

Consider toxins and carcinogens. Lead and asbestos were in use since antiquity; only in the 20th century did we deeply understand their health risks and thoroughly remove them from our environment.20 Mercury and other poisons were once prescribed as drugs; now all pharmaceuticals undergo extensive toxicity testing.21 Common occupational hazards once included inhalation of smoke or coal dust, or exposure to phosphorus, benzene, or even radium.22 Health concerns today, such as damage from microplastics, are subtle, long-term effects compared to what people routinely faced in the past.23

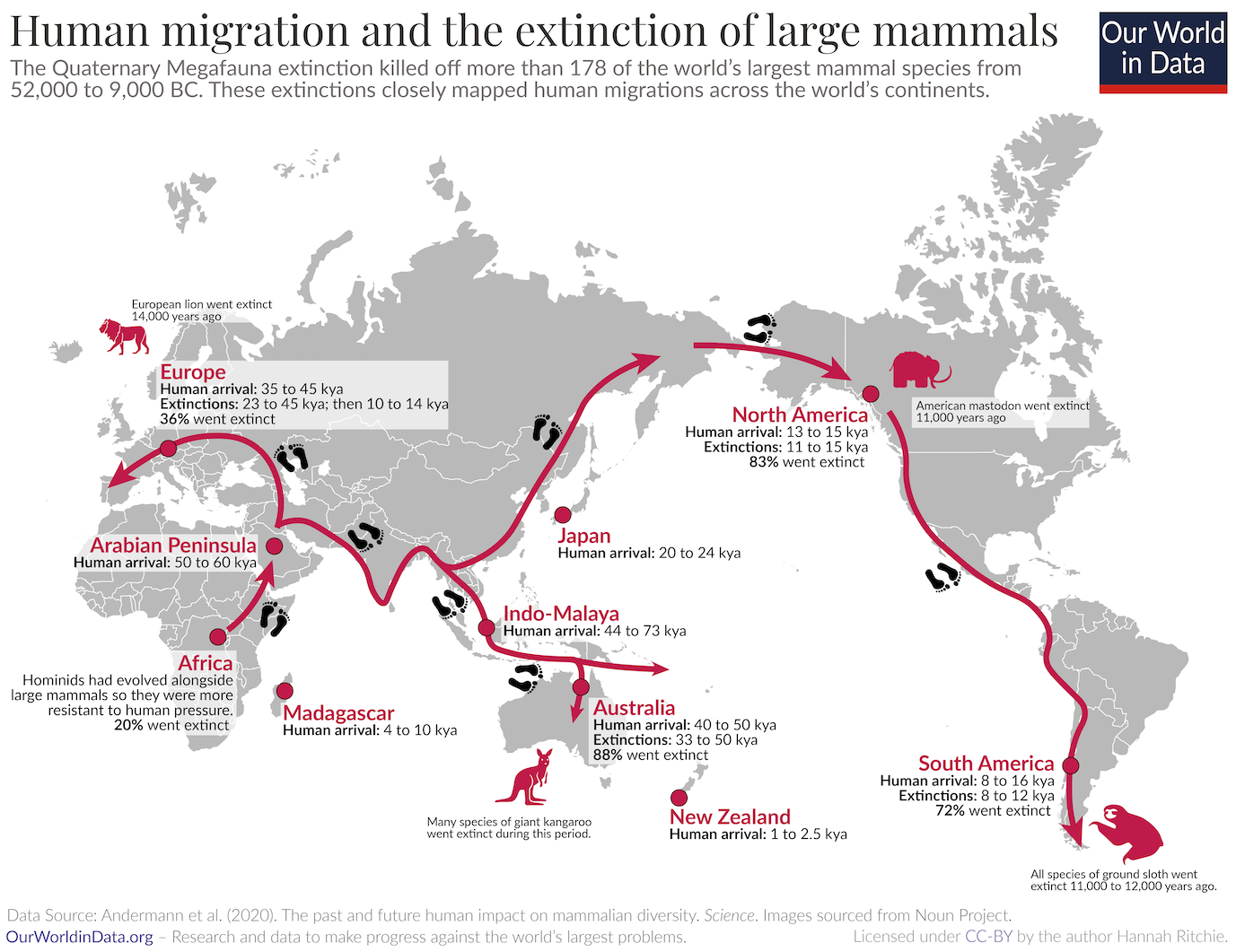

Our maintenance of the planet follows the same pattern: we are far more aware of, careful about, and able to control and limit environmental damage than ever before. Primitive hunters drove megafauna to extinction around the world. Early agriculturalists deforested large swaths of land via slash-and-burn, which one historian calls “undoubtedly the greatest ecological destruction in history.”24 In all such cases, those responsible had no concept of the downstream effects of their actions, no way to detect or measure them, and no scientific framework to understand them. Even if they had known what they were doing, they would not have been able to formulate a response, or communicate it to other tribes, or coordinate its implementation.

Contrast this with a modern example of unintended environmental consequences: the degradation of the ozone layer by chlorine-containing chemicals such as CFCs. The effects were located in a minute quantity of an invisible gas several miles above our heads. The consequences were even further removed, such as skin cancer from increased ultraviolet radiation. No society before the 20th century would have had the means to follow such a subtle chain of causation, or to link a chemical used in aerosols with skin lesions elsewhere on the globe, decades later. If CFCs had been invented in the Victorian era, rates of skin cancer would have increased mysteriously for decades without anyone understanding why—probably without anyone even noticing, since statistics on cancer incidence weren’t kept until the mid-1900s. Today, we have the infrastructure to detect the problem: a network of balloons, satellites, and ground-based instruments continually monitoring the composition of all layers of the atmosphere. We have the chemical knowledge to identify ozone, the geophysical knowledge to link it with ultraviolet radiation, and the medical knowledge to link radiation with cancer. We have the surplus wealth to invest in a scientific community that does all these things. We have the communications technology to spread the news when we discover problems like this. And we have the institutions to coordinate an international response, almost completely phasing out ozone-depleting chemicals worldwide.25

The acceleration of material progress has always concerned critics who fear that we will fail to keep up with the pace of change. Alvin Toffler, in a 1965 essay that coined the term “future shock,” wrote:

I believe that most human beings alive today will find themselves increasingly disoriented and, therefore, progressively incompetent to deal rationally with their environment. … Change is avalanching down upon our heads and most people are utterly unprepared to cope with it … Such massive changes, coming with increasing velocity, will disorient, bewilder, and crush many people.26

Toffler and others worried that as progress moves ever faster, the world will slip out of our grasp. But as we have just seen, the historical trend is the opposite: the world does change ever faster, but we get better at dealing with change. We can better comprehend change, thanks to scientific theories, instruments of measurement, monitoring systems, and global communications. We can better respond to it, thanks to technology, wealth, and infrastructure, especially our manufacturing and transportation infrastructure. And we can better coordinate that response, via corporations, markets, governments, and norms of international cooperation. Change has been accelerating ever since the Stone Age, but we can far better handle the changes in our fast-paced world than tribal hunter-gatherers, Bronze Age emperors, or medieval kings could handle the changes even in their relatively slow-moving ones. All of those societies faced existential risk from factors as simple as a shift in climate or a new pathogen: famine, plague, or war could and did cause civilizational collapse.27

Other critics have feared that, since technology is distinct from ourselves, progress therefore weakens us and makes us dependent on an alien object, or even enslaves us to our machines. As early as 1863, Samuel Butler warned:

Day by day… the machines are gaining ground upon us; day by day we are becoming more subservient to them; more men are daily bound down as slaves to tend them, more men are daily devoting the energies of their whole lives to the development of mechanical life. …

Our opinion is that war to the death should be instantly proclaimed against them. Every machine of every sort should be destroyed by the well-wisher of his species. Let there be no exceptions made, no quarter shown; let us at once go back to the primeval condition of the race. If it be urged that this is impossible under the present condition of human affairs, this at once proves that the mischief is already done, that our servitude has commenced in good earnest, that we have raised a race of beings whom it is beyond our power to destroy, and that we are not only enslaved but are absolutely acquiescent in our bondage.28

But if we are “slaves” to our machines, then the peasant farmer is a slave to the weather and the soil, and the hunter-gatherer is a slave to wild plants and game. To use the term “slavery” for any external influence or constraint is to destroy the concept. We exist in nature and must make our way in it; that is not slavery but natural law. We can choose to do so well or poorly, to have robustness or insecurity, to live using machines and systems of our own design, or at the mercy of luck and chance. To move from the latter to the former is not slavery but liberation.

Next: Chapter 2, part 2.

For more about The Techno-Humanist Manifesto, including the table of contents, see the announcement. For full citations, see the bibliography.

Correction: Quinine is effective against malaria. However, it was not available until the early 1800s; previously malaria was treated with cinchona bark. Thanks to Julian Jamison and Greg Salmieri for pointing out this error.

-

Whittaker, Flintknapping, 105-107 ↩

-

Kuhn and Stiner, “What’s a Mother to do?” ↩

-

Kremer, “Population Growth”; Clarke, “Mortality Trends.” ↩

-

Karnofsky, “Was Life Better in Hunter-Gatherer Times?”; Marciniak et al., “Reduced Health for Early European Farmers.” ↩

-

Diamond, “Worst Mistake in History.” See Introduction for more on Diamond. ↩

-

Boserup, Conditions of Agricultural Growth, 6; Richerson et al., “Agriculture Impossible during Pleistocene”; Matranga, “Seasonality and the Invention of Agriculture.” ↩

-

Mazoyer and Roudart, History of World Agriculture, 69. ↩

-

Ó Gráda, Famine: A Short History, 10. ↩

-

Carnegie, Autobiography, 94. ↩

-

Blockmans et al. The Routledge Handbook of Maritime Trade around Europe 1300-1600, 19; Bernstein, A Splendid Exchange, 81-82, 101. A notable exception is the Polynesians, whose navigational skills helped them expand throughout the Pacific islands. ↩

-

Semyonova Tian-Shanskaia, Village Life in Late-Tsarist Russia, 119. Even today, in the poorest regions, indoor air pollution is a top health hazard: see Ritchie, “Indoor Air Pollution.” ↩

-

Massey, “Sermon Against Inoculation.” Spelling and capitalization have been modernized. ↩

-

Almeida Marques, “Paths of Providence.” Rousseau was responding to Voltaire’s “Poem on the Lisbon Disaster,” which rebutted many of the apologists who said that the earthquake was a just punishment or that it was somehow for the best. ↩

-

Stoddard, Steel: From Mine to Mill, the Metal that Made America, 157. ↩

-

Waters, “Sea Monsters on Medieval Maps.” ↩

-

Coaston, “What’s Your Plan About Marriage and Dating?” ↩

-

Hadfield et al, “Real-Time Tracking of Pathogen Evolution”; Milken Institute, “COVID-19 Vaccine and Treatment Tracker”; Vanderslott, “Vaccination.” ↩

-

DeWitte, “Medieval Black Death”; Roser, “The Spanish Flu”; covid percentage is based on Our World in Data’s central estimate of excess deaths in “Estimated Deaths per 100,000 People.” ↩

-

Sohn, “Lead”; Dignam, “Control of Lead Sources in the United States”; Kakoulli, “Earliest Evidence for Asbestos.” ↩

-

Gaynes, Germ Theory, 53; O’Shea, “Two Minutes with Venus, Two Years with Mercury”; Junod, “FDA: A Short History.” ↩

-

Beer et al, “Systematic Review of Exposure to Coal Dust”; Jacobsen et al, “Phosphorous Necrosis”; “History of Benzene Use”; Orci, “Radium in Everything.” ↩

-

Balch, “Microplastics are inside us all.” ↩

-

Mazoyer and Roudart, History of World Agriculture, 126. ↩

-

Ritchie, “How we fixed the ozone layer.” ↩

-

Toffler, “The Future as a Way of Life.” ↩

-

E.g., Tigue, “Bronze Age Collapse.” ↩

-

Butler, “Darwin among the Machines.” ↩