Smart, rich & free

by Jason Crawford · July 8, 2017 · 2 min read

Why study the story of human progress?

50,000 years ago, our ancestors lived at the mercy of nature. They had stone tools, and the use of fire—and not much else. They had no agriculture: they survived by hunting and foraging. They had no medicine. They had small boats to travel short distances on water, but on land they had to walk, and anything they took had to be carried. They had language, but no writing. Of course, they had no science. And they had only the tribe to protect them: no police, no courts, no law. In short, their lives were characterized by abject poverty, superstition born of ignorance, and constant tribal warfare.

We have come a very long way. We live in buildings, not caves. We are surrounded by mass-manufactured products made of steel, glass and plastic. We extract vast sums of energy buried in the ground and we make it do our bidding. We have all the food we could want—so abundant and delicious that we have to restrain ourselves from eating too much. We have antibiotics and laser surgery. We zip around the world at hundreds (and maybe soon thousands) of miles an hour. We can communicate with anyone, anywhere, anytime, instantly. And all of this is made possible by a vast and rapidly expanding scientific knowledge of the world. Further, we live in relative peace and freedom, made possible by governments that maintain law & order—and the institutions of democracy and republicanism that keep those governments in check. In short, compared to our prehistoric ancestors, we are smart, rich and free.

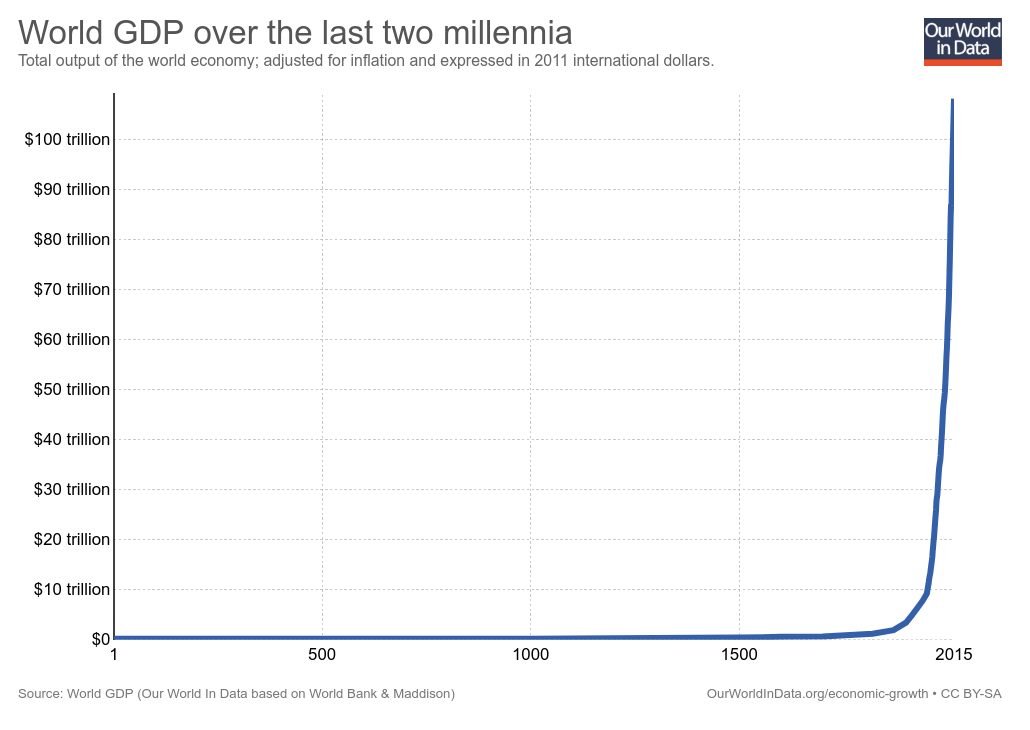

This story would be amazing enough in itself. But even more astonishing is that out of those 50,000 years, most of this progress has been made in the last 1% of that time. We owe the modern world to three revolutions—the Scientific Revolution, the Industrial Revolution, and the American Revolution—all of which are less than 500 years old.

Anyone who loves human life must, I submit, be at least a little awestruck by these facts. And any society that values life ought to ask itself three crucial questions:

-

How did we get here? What were the steps of this amazing journey?

-

Why did it take so long? Why did humanity have to suffer and die for tens of thousands of years before we finally found the keys to progress?

-

How do we keep it going? And even speed it up? Conversely, what could threaten to slow, stop, or even reverse it?

This is what Roots of Progress is about.

There are many theories about why this progress happened (and why it happened when and where it did). But to start I’m just concerned with what. What happened? My first goal is to get clear on that and to be able to summarize it and understand its structure.

I’m starting with technology and production—the “rich” part. But long-term I want to study the growth of science & knowledge as well, and also the progress in morality and politics.