Out of whole cloth

by Jason Crawford · April 21, 2018 · 12 min read

Ever since I read a history of cotton, I have been wanting to write a post on the story of textiles. Mechanization of the cotton textile industry was a crucial part of the early industrial revolution, showing up in any overview, such as How the Industrial Revolution Changed the World. But neither of those books gave me the story clearly and concisely enough. So I’ve been investigating more on my own.

It’s been a bigger project than I suspected, perhaps because my ambition for the post keeps growing the more I learn. So I’m going to checkpoint here and lay out the story as I understand it so far, together with my open questions.

Textile production is a complicated process with many steps, and the steps can be different depending on the type of fabric being produced. But to simplify, we can think of the main stages as preparation, spinning, and weaving.

“Preparation” is a general term I just made up to describe anything done to the raw, natural material to get it ready for spinning into yarn. Cotton and flax are harvested from the field, wool is sheared from sheep (and other animals), and like everything else in nature, these materials come to us in an inconvenient form. The fibers may be mixed with dirt or grease. Cotton bolls have seeds, which in some varieties are sticky and thus difficult to remove. Flax fibers must be broken out of the hard outer stem and separated from the stalk. And in all cases, the fibers start out as a tangled mess.

Spinning is the process of turning fibers into yarn, which can be woven. In spinning, the fibers are drawn out to make a long string, and twisted together so they lock with one another, forming a single, strong piece of yarn. (In case you’re confused, as I was, about the relationship between yarn and thread: “yarn” is the more general term; thread is a type of yarn. Sources differ: thread is sometimes defined as yarn intended for sewing, but it is also the input to weaving. I’ll use the terms loosely here.)

Weaving is the process of interlacing threads perpendicular to each other to create a fabric. There are many different types of weaves that produce different patterns and textures, and even visual designs when different colors of thread are used, but we’ll ignore this for simplicity right now.

There can be more stages involved: for instance, treating with chemicals to clean, bleach, or dye the yarn, or to protect it against abrasion on the loom; or printing patterns on finished cloth. And I haven’t even mentioned sewing, which is needed to create most actual usable consumer goods. Further, weaving is not the only way to create fabric (yarn can be knitted, or fibers can be pressed into felt without even being spun), and yarn is not the only thing that can be woven (straw can be woven into mats or baskets). But again, for simplicity, we’ll ignore all this and focus on the basic process of woven textile production.

In the pre-industrial world, every stage of the process was done by hand—often with hand tools, sometimes literally with the fingers, as in the case of picking seeds out of cotton lint.

A process called carding untangles the fibers (and can help remove debris) by running them over a card with metal pins sticking out of it, sort of like a brush. An alternate process, “combing”, passes the fibers through long metal spikes instead of short pins, which lays long fibers parallel and removes shorter fibers; I think this produces a higher quality of yarn (when done to wool, I think it is the main difference between “woolen” and higher-quality “worsted” fabric). Combing is an optional process, but I’m still a little unclear on whether it completely replaces carding, or if you would ever do both to the same material. In any case, a mass of fiber that has been sufficiently straightened and stretched out into a narrow bundle, ready for spinning, is called a sliver (rhymes with “diver”), or, if drawn out a bit thinner and given a slight twist, “roving”.

The simplest way to spin yarn, going back to prehistory, is with a spindle. This is nothing more than a stick, typically with a weight and/or a hook on one end. With one popular type, the drop spindle, you simply hook a piece of the roving, hang the spindle from it, and literally spin the shaft as you draw the fiber out, which gives it the necessary twist. The weight gives the spindle momentum and keeps it turning at a steady pace. When you have a couple of feet of yarn, wound tightly enough, you stop, wind the yarn onto the spindle itself, and then hook the top of it to spin the next section. This video shows the process. A “distaff”—basically just another stick—can hold the roving; tucked into a belt or held on a strap, it keeps both hands free.

If this sounds slow and tedious, that’s because it is. A faster method is to use a spinning wheel. A spinning wheel also contains a spindle, but sets it in a frame which can stand on a floor or table, and attaches it to a large flywheel. (This flywheel is the most noticeable part of a spinning wheel, and if you’re as ignorant as I was, you might think the yarn goes over the wheel itself. Nope! As far as I can tell, the wheel is just there to turn the spindle at a steady pace.) In advanced spinning wheel designs, one continuous spinning motion serves to both twist the fiber into yarn and wind it onto the spindle, so there’s no need to stop and “wind on” the yarn. Some wheels also can be turned with a foot pedal; this, plus having the whole thing in a frame, leaves both hands free to draw out the fibers and feed them onto the machine. Altogether this is much more efficient than a spindle. This video is the best I found to see the operation of the mechanism.

Weaving is done on a loom. One set of threads, called the warp, is stretched parallel, while another thread, called the weft, is interlaced between them. The basic action is: half the warp threads are pulled away from the other half, creating a gap between them. The weft is pulled or pushed through the gap, and then pushed tight against the rest of the woven fabric; this action is called a pick. Then the warp threads are reversed, the other half being lifted up to invert the gap, and the action is repeated, with the weft going in the other direction. (In a plain weave, every other warp thread is lifted; in more sophisticated or pattern weaves, any subset of the warp might be lifted in any pick.)

There are many types of looms. One of the simplest involves hanging the warp threads vertically with weights. In another primitive loom, the “backstrap loom”, one end of the warp is tied to a fixed pole, and the other end to a strap around the weaver’s back; the weaver adjusts the tension on the warp by leaning backwards into the strap.

The type of loom used at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution was more advanced. The whole machine stood in a large frame, with the warp threads running horizontally through it. The warp was lifted by strings connected to foot pedals, and the weft was thrown back and forth on a “shuttle”, a small piece of wood that held a spool of thread. A comblike structure called the reed would push the weft down after each pick. A small loom could be operated by one person, but obviously the fabric could not be wider than the weavers’ arms, since they had to pass the shuttle through by hand. To weave a wider cloth required multiple weavers, who would throw the shuttle back and forth.

This was the state of things by the early 1700s: a highly manual process, done with the aid of sophisticated machines, but still completely dependent on the time and attention of skilled craftsmen, and largely done in the home—literally a cottage industry. Each weaver needed several spinners to supply him, and each spinner relied on a supply of cotton, wool, or flax that was collected and cleaned by hand. Not only was the process time-consuming and tedious, it took practice. The quality of the output depended on the skill of the artisan; poor work would result in a product that was lumpy, uneven, or rough.

The entire process had stayed largely the same for centuries. But it was all about to change.

Over the course of several decades starting in the 1700s, this entire process was revolutionized by automation. In short, we invented machines to do almost every step of the process. And machines, it turns out, can work faster, better, and more consistently than people. The result was an enormous reduction in the cost of fabric, or conversely, an enormous increase in the productivity of each worker—and at the same time, a product that was of higher and more consistent quality. I’m still trying to understand exactly how this happened, but here’s what I know so far.

First, this wasn’t the result of any single invention. There are a few inventions that typically get called out as the major ones, and certainly some were more important than others, but there were many inventions, over a long span of time, and the progress that resulted was the accumulation of many incremental improvements. Also, these improvements were the work of many different inventors and businessmen—although one name, Richard Arkwright, stands out as a driving and integrating force. Also, for reasons that are not entirely clear to me, the story was centered on a single type of fabric: cotton.

The major inventions seem to have happened more or less in the reverse order of the process itself: that is, the first big improvements were in the last step of the process, weaving, and some of the last were in the earliest stages of harvesting and cleaning. This may not have been a coincidence: an improvement at any stage creates a greater demand for the input to that stage, increasing the incentive to improve the earlier stages. More generally, an improvement at any part of a multi-stage process like this simply shifts the bottleneck to a different part of it.

The first major invention seems to have been the “flying shuttle” (1733). I mentioned above that weaving a wide cloth requires at least two people to throw the shuttle back and forth. The flying shuttle solves this problem. Rather than being thrown by hand, a flying shuttle rides on wheels, and is kicked back and forth by blocks on either side of the loom. The blocks are tied to a cord with a single handle that can be yanked by the weaver. A hard tug on the cord pulls both blocks in toward the middle; whichever one the shuttle is next to gives it the needed push. When the shuttle arrives at the far end, its momentum pushes that block backwards, resetting it for the next pick. See it in operation here. I think there are some other details needed to make this work, but I don’t understand them yet. In any case, the flying shuttle at least doubled the productivity of weavers.

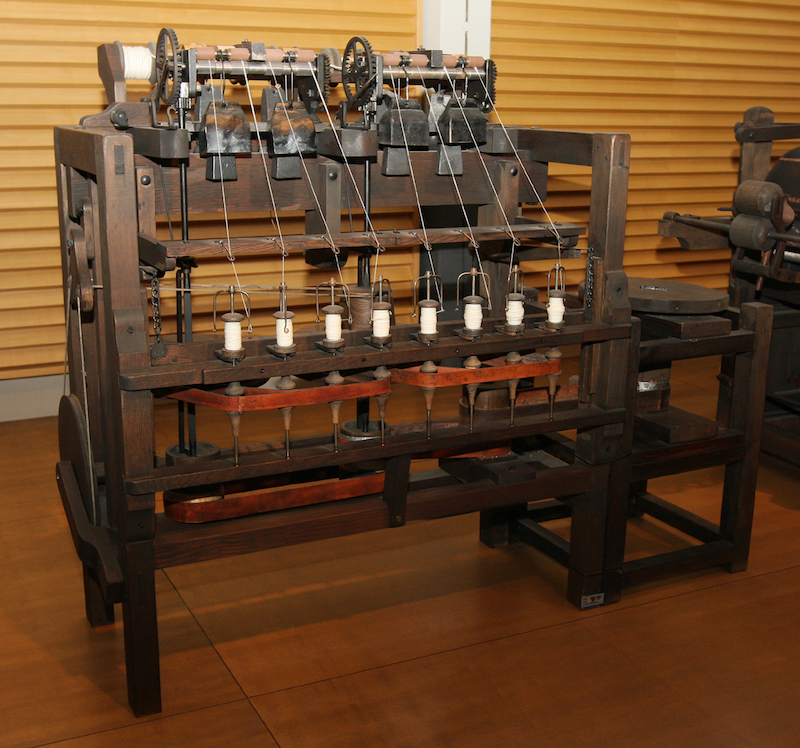

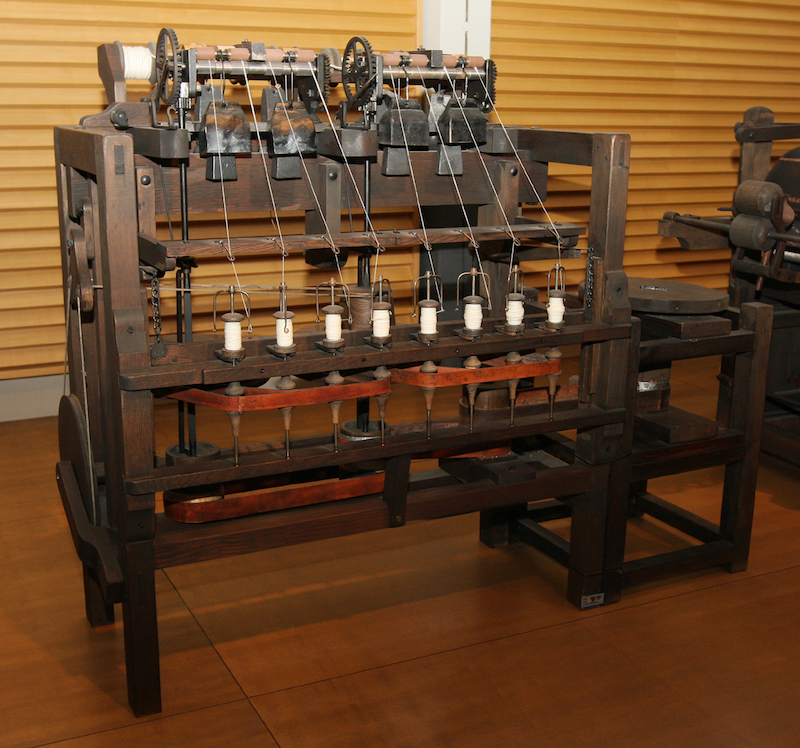

Spinners were already at a productivity disadvantage to weavers: even before the flying shuttle, it took several spinners to supply one weaver with yarn; after it the ratio was even worse. The productivity of spinners was improved by a number of inventions in the late 1700s. The “spinning jenny” (1764) split the roving into several strands, so multiple threads could be spun at once (initially eight, later I believe over a hundred). This was a huge advance. However, I believe it was still largely operated by hand, and it had some problem that prevented it from creating a very strong cotton thread (in fact, it was only strong enough to be used for weft, not warp, and so weavers would combine cotton weft with linen warp, creating a blend called “fustian”). A later invention, confusingly called the “water frame”, used rollers to draw out the fibers, and was able to create stronger thread (and thus led to pure cotton fabric). There were multiple pairs of rollers, each moving a bit faster than the previous, so that the roving was stretched thin as it went through them. The key was to space the rollers carefully, just longer than the length of a fiber: too close together, and a single fiber would get caught in two pairs of rollers at once, which would break it; too far apart, and the roving would be pulled completely apart. The initial version of the water frame, however, might not have been able to spin multiple threads at once like the jenny. Eventually, through many iterations, spinning machines were created that both removed all the focused attention and manual dexterity from the process, and could spin many threads at once with a single human operator.

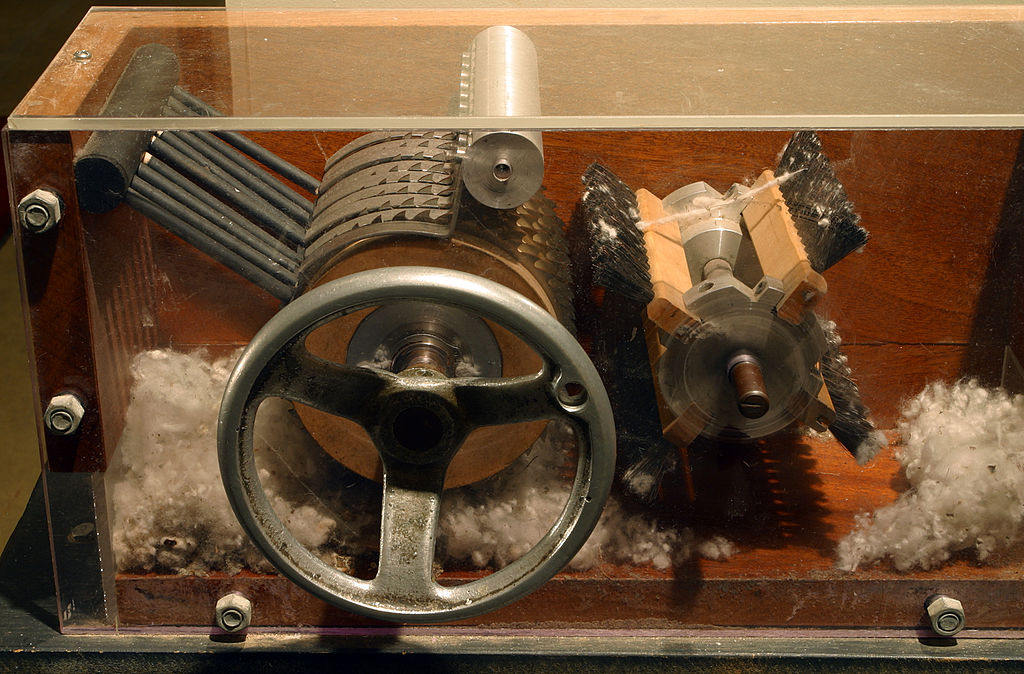

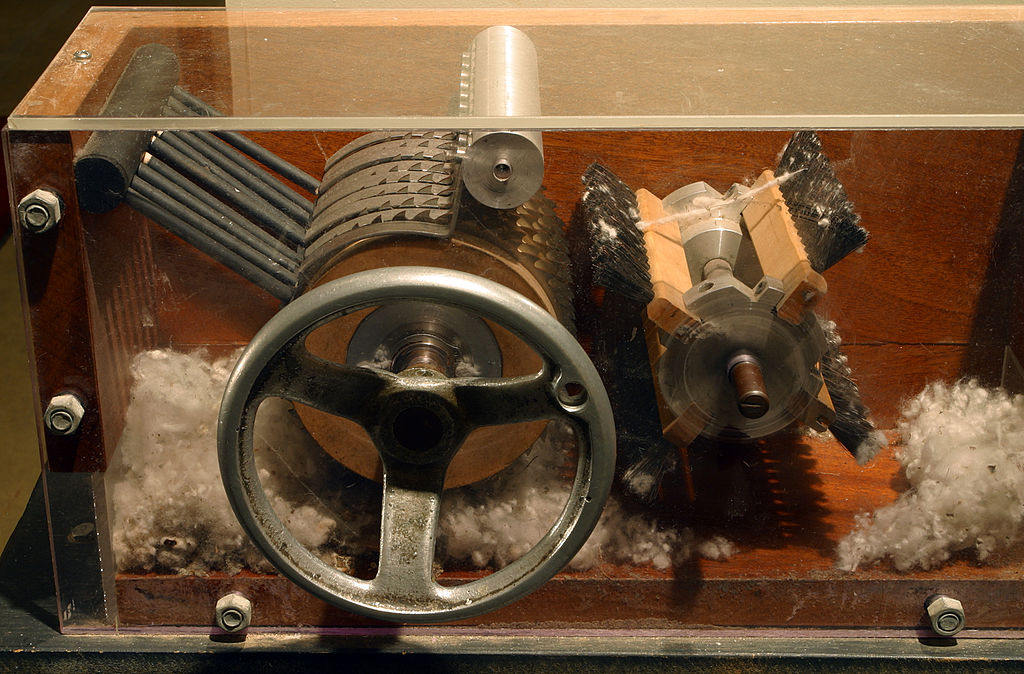

These advances created a great demand for cotton—which still had to be picked, cleaned and carded by hand. Multiple inventions helped with this, including automatic carding machines, but perhaps the most important (and certainly the most famous) was Eli Whitney’s cotton gin (1793). The cotton gin automated the process of separating the sticky seeds from cotton lint, a slow, tedious manual process. It is a simple device: a box with a wire screen, and a rotating drum with metal teeth. Freshly picked cotton bolls are dumped in the side of the box opposite the drum. As the drum rotates, its teeth reach through the screen and snag bits of cotton fiber, which they pull through the screen (the screen keeps the seeds from coming along). Basically, instead of pulling the seeds out of the cotton, the cotton is pulled away from the seeds. This enormously improved the productivity of cotton farming in the American South, transforming it from a barely profitable crop to a hugely profitable one (as an unfortunate side effect, this may have entrenched the institution of slavery—but that is a subject for another post).

Before too long, many of these processes were connected to power: first water mills, later steam engines, and eventually electricity. The power loom was invented in the late 1700s, and must have required some key inventions I don’t yet understand to make the machine more automatic. (One challenge of automated weaving is all the things that can go wrong: if a single thread breaks or gets tangled, the whole machine needs to be stopped immediately, and the problem fixed before continuing.)

To summarize: the productivity of the textile manufacturing process, and thus the cost of cloth, was improved by orders of magnitude starting in the 1700s through a series of inventions from multiple inventors that, in aggregate, transformed it from a fully manual process to a fully automated and powered one.

Once the initial inventions removed the manual labor and careful fingerwork from the process, subsequent inventions, continuing through the 1800s and 1900s, focused on improving speed, efficiency, and quality. The result is the modern textile industry: large factories turn out enormous amounts of high-quality fabric at extremely low cost.

That’s the outline of the story as I understand it so far. I’d like to get clearer on the details. And there are still many things I’d like to understand:

-

Just how much did productivity improve? I’d love to quantify this. How many yards of thread per hour could a spinner produce with each of the above machines? How many square feet of cloth could a weaver output? Conversely, how many person-hours did it take to go from cotton in the fields to a shirt on the rack?

-

What was the effect of this productivity? Basic economics says that the cost of each output should come down, and simultaneously that real wages for the workers should go up. What actually happened, historically? And what were the social consequences? Eventually large textile mills were opened, such as the ones in Lowell, Mass., that offered new jobs and newfound freedom especially for young women.

-

Why cotton? Wool and linen are good materials, and I think they were more commonly used, at least in England, before the Industrial Revolution. Why did England switch to cotton in the course of this mechanization, and why does cotton dominate textiles today?

-

Why weaving? As I mentioned, fabrics can be made by knitting, felting, etc. Why are most of our fabrics woven?

-

For what matter, why fabric? What are the benefits of textiles vs. leather or other materials that could substitute?

-

What was the real contribution of Richard Arkwright? Arkwright was clearly a central figure in this story in the 1700s. He seems to have been an unpleasant character who was generally disliked, and there are plenty of stories of him supposedly stealing inventions or treating business partners badly. However, there are also hints that he was an indispensable driving and integrating force.

-

What was the reaction from craftsmen? Mechanization was fiercely opposed by traditional spinners and weavers—like many other innovations, as I am discovering. In this instance the reactions were particularly violent, including the Luddite movement that went around smashing machinery (I used to think the Luddites were a religion, like the Amish but with a rioting streak; it turns out they were a political movement).

-

Why did everything take so long? I’ve already asked this specifically with respect to the cotton gin, but the more I’ve read about these inventions the more it seems to apply to all of them. The flying shuttle seems as simple as the cotton gin, the spinning machines not much more complicated. Why did no one create them for centuries?

But all the above might take multiple posts.

Thanks to Eric Norman and Doug Peltz for commenting on a draft of this post.

Relevant books

A Brief History of How the Industrial Revolution Changed the World