Learning with my hands

by Jason Crawford · April 1, 2018 · 4 min read

A few months ago I read a history of cotton, which led to a post on the cotton gin and one on pesticides. But I really wanted to write one that explains textiles overall, including the dramatic increases in productivity from mechanization that were part of the early Industrial Revolution. I wanted to do for textiles what I did for concrete.

But I still have so many questions. What exactly was the flying shuttle? How did it work? For that matter, how did looms work before? I mean, I’ve seen looms and I get what they are basically doing, but… why do they have so many parts? And similar questions for the “spinning jenny” and the spinning wheel.

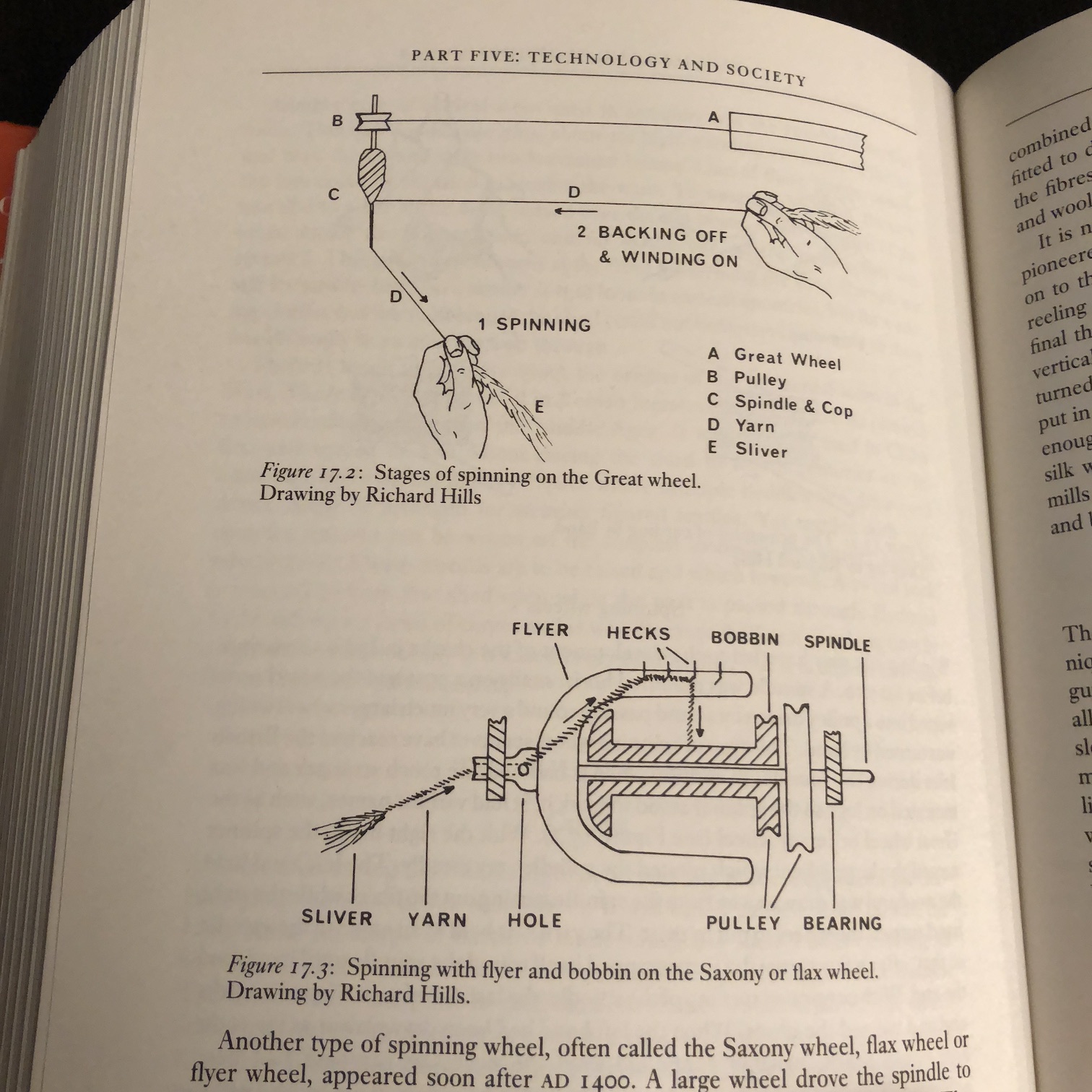

So I’ve been doing more research, from Wikipedia articles to the thousand-page Encyclopedia of the History of Technology. But when it comes to sophisticated machinery performing intricate processes, it’s really hard to understand from a written description, especially when there’s so much terminology. Everything ends up sounding like: “In the flying jenny, the thread is wound through a hole in the bobbin, past the reed, where it beats against the whorl. The operator must take care to prevent the shuttle from stretching the treadle too far, for fear of snarling the weft. Obviously.”

Diagrams barely help. Videos are much better, and YouTube has been great (this video finally showed me how a flying shuttle works, which no written description ever made clear, even though it’s extremely simple). But it slowly dawned on me that in order to truly understand these machines, I have to see them in person—or better yet, use them.

One possibility is to visit a museum. Many “textile museums” are actually either art galleries or just old mills that got converted into historical sites or national parks. However, I’ve just discovered the Antique Gas & Steam Engine Museum, which I’m excited to visit. Their Weavers Barn is “a 4,000 square foot facility where we house and use over 50 looms as well as many of the related tools needed to turn fiber into cloth, including spinning wheels and carders, warping boards and swifts, and bobbin winders and shuttles. We are a working museum with more than 95% of our exhibits operational.” Cool!

Even better than just a museum, I thought, why not take a class where I can try my hand at these machines? No better way to learn than by doing. And if I’m going to take that approach with spinning and weaving, why not apply it to all the pre-industrial crafts? Metalworking, carpentry, pottery, masonry….

Before I knew it, I found myself at The Crucible, a maker space for industrial arts in Oakland. At their open house, we saw demonstrations in blacksmithing and glassblowing, and I got to try my hand at stone carving, working a block of alabaster with hammer and chisel. Right away, I could see that hands-on experience would teach me a lot. Just trying to cut a simple groove in the rough face of the stone—an arbitrary task to give myself a goal, for a few minutes of play—I started learning how subtle it is to work with materials. The angle of the chisel against the face of the rock makes all the difference. Hold it too close to perpendicular, and you’re just making a hole in the block, or cracking it in two. Hold it too close to parallel, and the chisel slips along uselessly. You have to get the angle just right to get the cut you want—and since the rock is uneven, the ideal angle is constantly changing as you work across the surface.

This parallels what I’ve been reading about textile making: it wasn’t just time-consuming and labor-intensive, it was a skill. It required manual dexterity to produce a quality product. Thread, for instance, is ideally a consistent thickness along its length, but a novice spinner will often create lumpy thread, leading to coarser fabrics. Spinning quality thread requires practice. Mechanizing the textile manufacturing process not only saves human time and effort in producing goods, it also eliminates the investment in skill-building that every spinner and weaver must go through. In a sense, we build the muscle memory into the machines, encoding the implicit knowledge of the master craftsman in the solid form of spindles and gears. The resulting output is not only cheaper, but higher-quality and more consistent—mastery made mundane.

So by this point I’ve already signed up for intro classes in spinning and blacksmithing… but someone may have to hold me back, because I’ve discovered that this rabbit hole goes much, much deeper.

Asking friends about where one can try crafts like this, I got connected to Kiliii Yüyan, indigenous Nanai photographer, journalist, and kayak-builder. Messaging me from the Bering Sea off the coast of Alaska (“internet is pretttty slow over here”), he said that “the only and best place to learn this is at the Rabbitstick rendezvous, in Rexburg, Idaho, in September each year. It’s a primitive skills gathering, where the best and brightest practitioners in the world get together to teach and learn skills that are stone age up to pre-modern. People come from all over the world to learn there.” Basically it’s a week-long camping trip, and all day every day there are workshops and demonstrations from instructors like Kiliii on everything from knife making to shelter building to braintanning (that’s a form of hide tanning using a solution of the animal’s own brain. (!))

But here’s the thing: it’s not the only one. This is an entire subsculture that has been around for decades. In addition to Rabbitstick, I quickly discovered Winter Count, Earthskills, and many more, as well as The Bulletin of Primitive Technology, a magazine that was published for 25 years.

I haven’t signed up for any of these gatherings yet… but at this rate, I might be an instructor there before long. In any case, I’m looking forward to learning, not just through books, but through my hands.