Learning the loom

by Jason Crawford · May 27, 2018 · 7 min read

In my quest to understand textile production, and in the spirit of learning with my hands, I took a weaving class to learn how to use a handloom. Looms, even manual ones, are complicated machines, with many moving parts, and I found them hard to understand from diagrams. My goal was to learn how one works, by using it. I took the class at San Francisco Fiber, from owner Lou Grantham, who has been weaving and teaching weaving for something like fifty years.

The goal for the day was a scarf, about two and a half feet long and seven inches wide, made from woolen yarn. A scarf is about the simplest thing you can make, since it’s just a rectangle of cloth. Once you weave the cloth itself you’re pretty much done. And a narrow piece of cloth is easiest, because as I found out, the most time-consuming part of weaving is setting up the loom.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. My goal in this post is to explain to you how a loom works, as clearly as I now understand it. To get there, you need to understand what problem each piece of a loom is solving. To do that, we’re going to start from the simplest possible loom, and build up to the kind of loom I used, one step at a time.

Simple looms

Let’s review the basics: Weaving is a process of making cloth by interlacing threads perpendicular to each other. A loom is any machine or device that holds the threads and helps you weave them. You stretch out one set of threads, the “warp”, parallel on the loom. Another thread, the “weft”, goes over and under the warp threads, back and forth, again and again, to create the woven fabric.

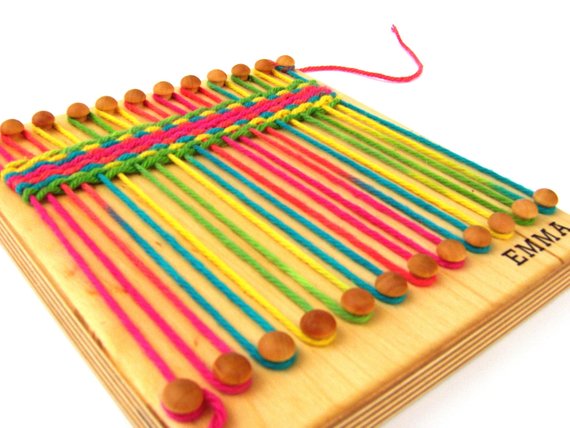

The simplest possible loom is just a board or frame with pegs to hold the warp, such as this one:

Using a needle, a hook, or just deft fingers, you interlace the weft through the warp threads, again and again, back and forth. As you can imagine, it’s excrutiatingly tedious, which is why looms like this are sold today only as novelties or toys for children (as one mommy blogger says, “it’s teaching my daughter a great deal of PATIENCE”).

The shuttle

The first problem you might notice is that each time you pass the weft through once, you have to pull it all the way through, taking up all the slack. You can see the issue in this video (you only need to watch for about 30 seconds):

This might be fine if you’re only making a pot holder, but if you’re even making something as long as a scarf, you’re going to have a lot of weft. Pulling every inch of it through every time gets annoying.

The solution is to wrap the weft around a small piece that holds it, spooled up, and to pass the entire thing back and forth. This piece is called the shuttle (it shuttles back and forth). You unspool only as much thread as you need to get across, each time.

This photo shows a simple frame loom with two shuttles: one with purple thread is partially through the warp; the other, with yellow thread, is waiting on the side:

Making space

But there’s another problem, which is that it’s difficult to pass the weft over and under each warp thread. And our solution to the previous problem has just exacerbated this one, because now instead of pulling the weft through with a hook, we have to push the entire shuttle through.

It would be much easier if you could just lift up every other warp thread, creating an open space to pass the shuttle through. And in more advanced looms, this is exactly what you do. The space between the warp threads is called the shed.

The easiest way to create a shed is to take a flat stick, push it over and under the warp threads, and then turn it to separate them, as seen in this video (again, you only need to watch for 30 seconds or so):

It’s certainly easier to pass the shuttle through this way, but overall the process hasn’t been improved much, because inserting the shed stick is not much easier than passing a hook through the warp threads. You still have to push it over and under them by hand each time.

If you’re very clever, you might figure out that using two sticks, you can cut your work in half. You can leave one of them in the warp through the whole process, so you only have to set it up once. Now every other time, your work is already done. But half the time, you still need to take the second stick and weave it through the warp again.

One modern loom manufacturer has created a device for this, a comb-like instrument with teeth spaced just right to push down half the threads, leaving the other half in place. According to the sole, 3-star review, it doesn’t work very well: “Too many times the wrong warp threads fall between the dents, or two consecutive warp threads get pushed down.”

We’re going to need something better.

The heddle

So how can we create the shed quickly and easily every time, alternating which warp threads are up vs. down, but without having to interlace a stick by hand on each pass?

Well, we can’t do it with any rigid piece that goes across the loom. Any piece that goes all the way across will get in the way when the warp threads need to switch places: that’s why we’re constantly removing the shed stick and replacing it.

To avoid this, we need pieces arranged vertically. Let’s run every other warp thread through a little loop that is attached to a cord, wire, or thin stick. This is called a heddle. The other threads go between the heddles, leaving the warp threads free to move up and down, independent of each other.

Then let’s put the heddles in a frame, so they can be moved together. When we lift the frame, half the warp threads are lifted, leaving the other half down and creating a nice shed. To create the opposite shed, we lower the frame:

This is tedious to set up, because you have to pull every thread individually through the heddles (just watch about 30 seconds of this video):

But it’s worth it for the speed improvement. Once a heddle loom is set up, weaving can be done relatively quickly: raise the frame to create the shed, push the shuttle through the shed, then lower the frame to create the opposite shed, and push the shuttle back the other way. Repeat as needed.

Getting fancy

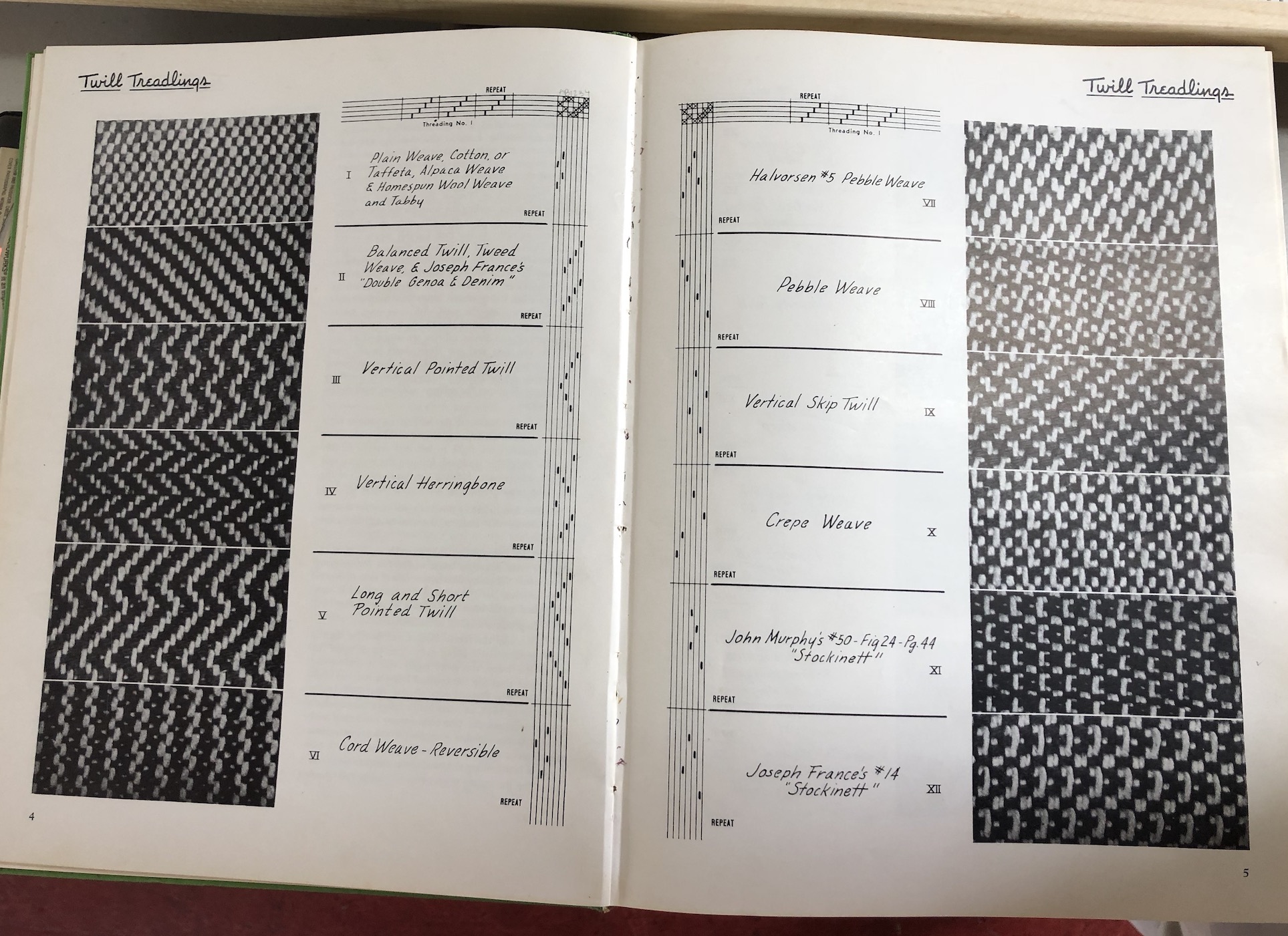

This solution works to create a “plain weave”, where the weft just goes over, under, over, under, in the simplest of patterns. But there are many more sophisticated patterns.

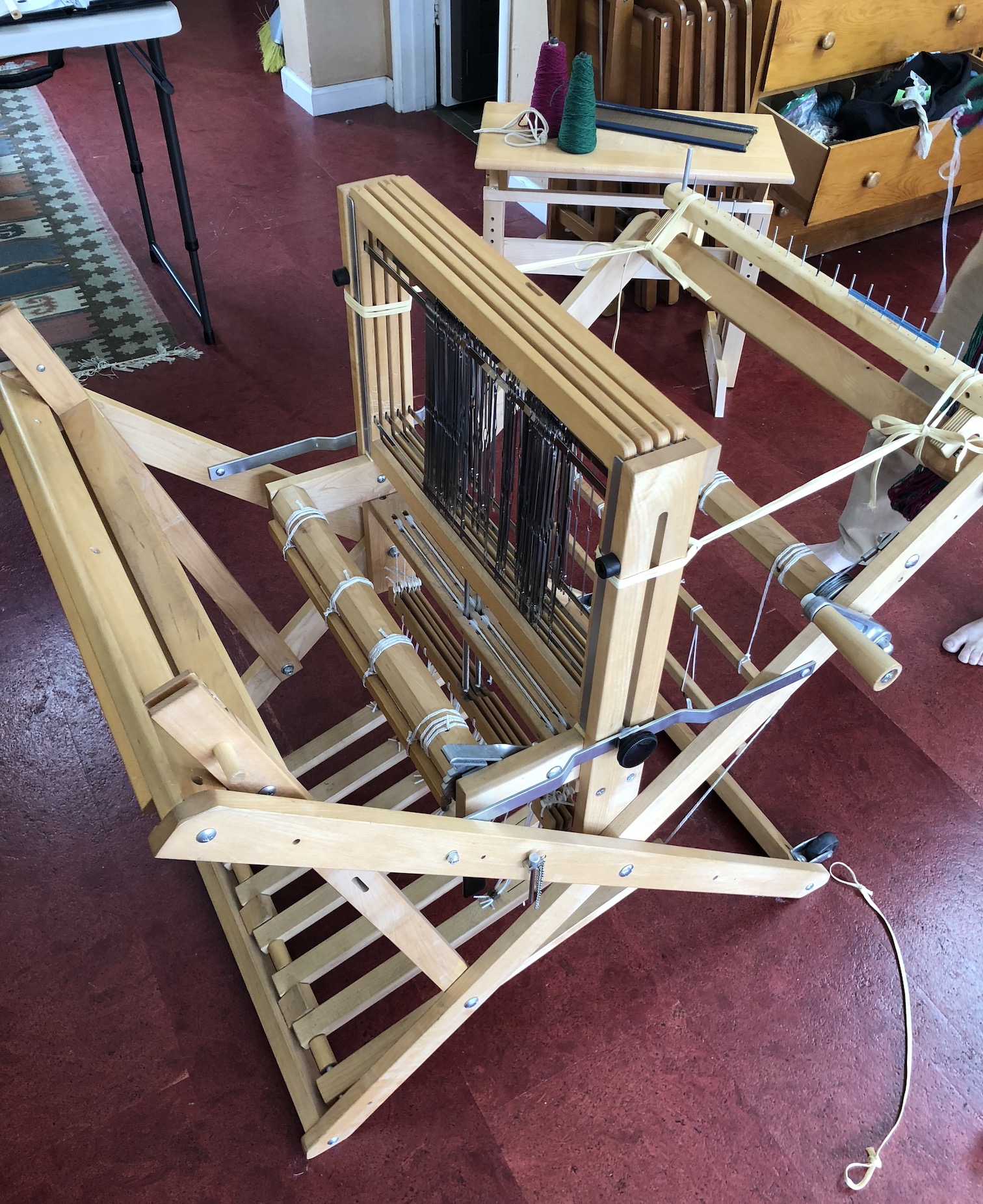

To create an advanced weave such as a twill or herringbone, you need more than one set of heddles. The handloom I used had four wooden heddle frames, with metal wire heddles:

Every warp thread (not just half of them) went through a heddle, with one quarter of the threads attached to each frame. Here’s the loom partway through setup:

The frames are lifted by pedals. Since every thread is attached to a frame, you never need to lower a frame, you just lift the other frames. This is a speed advantage versus constantly reaching forward and adjusting the placement of the frames by hand.

With four frames, you have more options. You can still do a plain weave by lifting frames 1 & 3 together, then lowering them and lifting frames 2 & 4 together. But you can also the diagonal stripes of a twill using a four-part sequence: first 1 & 2, then 2 & 3, then 3 & 4, then 4 & 1.

The frames were controlled by six pedals, corresponding to the six ways you can lift two of the four frames at once. The leftmost two pedals were set up to correspond to the alternating pattern of the plain weave, while the rightmost four pedals implemented the twill, both as described above. But by combining them in various sequences, all the patterns shown above and more can be created.

The reed

To explain the last piece of the handloom, I need to mention one final problem that I’ve been glossing over.

After you push the weft through, you don’t want to just leave it in place. You need to push it up against the woven fabric you’ve made so far, so it’s lying right next to the most recent thread you laid down.

In peg or lap loom, this can be done with the fingers, or with a comb-like tool. In the simplest heddle looms, with the heddle frames moved by hand, the heddles can be used for this purpose: you pick up the frame, pull it towards you to push the weft thread back, and then put it back in its new position. (You might have noticed both of those techniques in the videos above.)

By the time we get to a four-frame handloom, this isn’t going to work anymore. The frames are in slots; they only move up and down, attached to the pedals. So now we need a dedicated piece to push the weft down. This piece is called the reed, and it’s just a set of slots that the warp threads go through. It’s tedious to pull each warp thread through a slot, but it’s no more tedious than pulling them through the heddles.

Again, all of this setup investment pays off in speed: you move faster when you’re not constantly picking things up, putting them down, or reconfiguring the machine.

Making a scarf

Preparing the loom, as described above, took a couple of hours. First I chose colors and a pattern (the red central stripe, with green stripes on either side). Despite my previous spinning experience, we started with manufactured yarn.

Then we measured how many threads we’d need: 56, for a 7-inch piece of cloth with 8 threads per inch. We measured out the right length of thread for the warp, and stretched it across the frame. Next, each thread had to be pulled through the heddles and the reed, as described above.

But once the setup was done, I was able to weave like this:

I tried a plain weave, a twill (including some zig-zagging), and a bit of that pebble weave in the middle.

That’s the shuttle in my hand there; the weft thread was on a spindle in the middle. The spindle could only hold so much thread, so multiple times I had to go refill it from a spool. That could be done very quickly using this little crank-and-screw mechanism:

When you’re done, there’s several inches of warp thread that you can’t finish—you can’t weave right up until the end, because of the way the warp is tied on. So you just tie off the warp by making little knots. I guess that’s why scarves have tassels.

Finally we washed the scarf in warm water, to shrink it. (OK, Lou did this part for me!)

After five hours, I had my scarf.

Not bad for about half a day’s work!

If you’re in the Bay Area and want to take classes with Lou, check out her class schedule.