“Someone has to get hurt, occasionally”

How factories were made safe

by Jason Crawford · September 12, 2021 · 21 min read

Angelo Guira was just sixteen years old when he began working in the steel factory. He was a “trough boy,” and his job was to stand at one end of the trough where red-hot steel pipes were dropped. Every time a pipe fell, he pulled a lever that dumped the pipe onto a cooling bed. He was a small lad, and at first they hesitated to take him, but after a year on the job the foreman acknowledged he was the best boy they’d had. Until one day when Angelo was just a little too slow—or perhaps the welder was a little too quick—and a second pipe came out of the furnace before he had dropped the first. The one pipe struck the other, and sent it right through Angelo’s body, killing him. If only he had been standing up, out of the way, instead of sitting down—which the day foreman told him was dangerous, but the night foreman allowed. If only they had installed the guard plate before the accident, instead of after. If only.

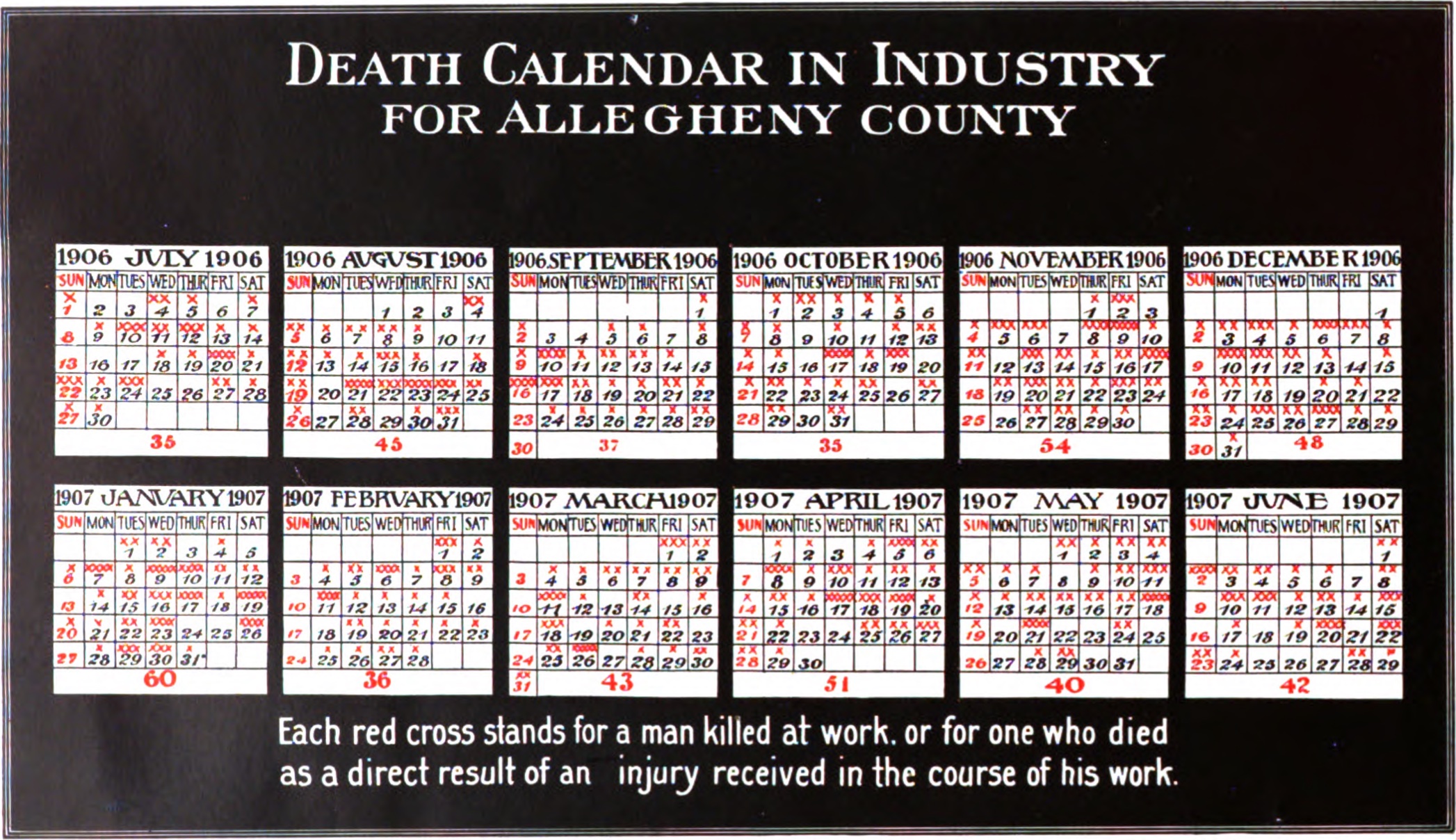

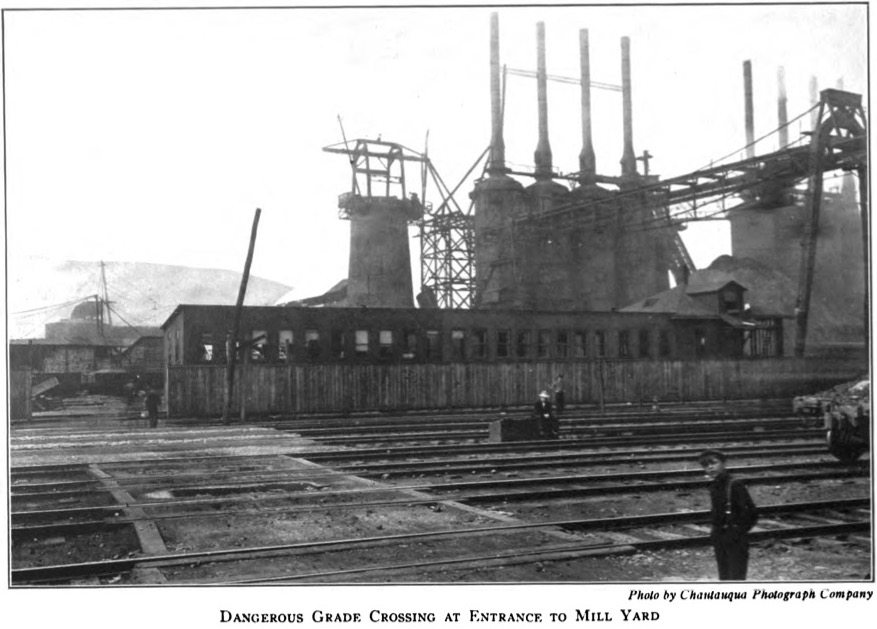

Angelo was not the only casualty of the steel mills of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania that year. In the twelve months from July 1906 through June 1907, ten in total were killed by the operation of rolls. Twenty-two were killed by hot metal explosions. Five were asphyxiated by furnace gas. Thirty-one fatalities were attributed to the operation of the railroad at the steel yards, and forty-two to the operation of cranes. Twenty-four men fell from a height, or into a pit. Eight died from electric shock. In all, there were 195 casualties in the steel mills in those twelve months, and these were just a portion of the total of 526 deaths from work accidents. In addition, there were 509 other accidents that sent men to the hospital, at least 76 of which resulted in serious, permanent injury.

In 1907, according to a report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the overall fatality rate in the iron and steel industry was about 220 per 100,000 full-time workers. By 2019, however, that rate had fallen to only 26.3 per 100,000, a reduction of almost 90%.

The story of workplace safety illustrates both the serious problems that progress can cause, and how the solution to those problems can be found in further progress. It’s a fascinating story in its own right, and in it we find lessons about safety in general, about liability law, and about the early history of capitalism.

The dangers of early factories

The Industrial Revolution created a dramatic boost in labor productivity through mechanization, the application of power, and the institution of the factory, which reorganized tasks and workers into a new mode of production. This led to vastly higher growth rates in GDP per capita and ultimately in real wages. But the very same elements—factories, machines, energy—created new risks that neither workers nor management were prepared for.

The pre-industrial world had plenty of dangerous jobs: mining for coal or metals, tending a blast furnace, sailing in the merchant marine. And of course, craftsman’s shops often posed risks from sharp tools or high heat (just ask Johnny Tremain). But the industrial factory brought a new set of risks.

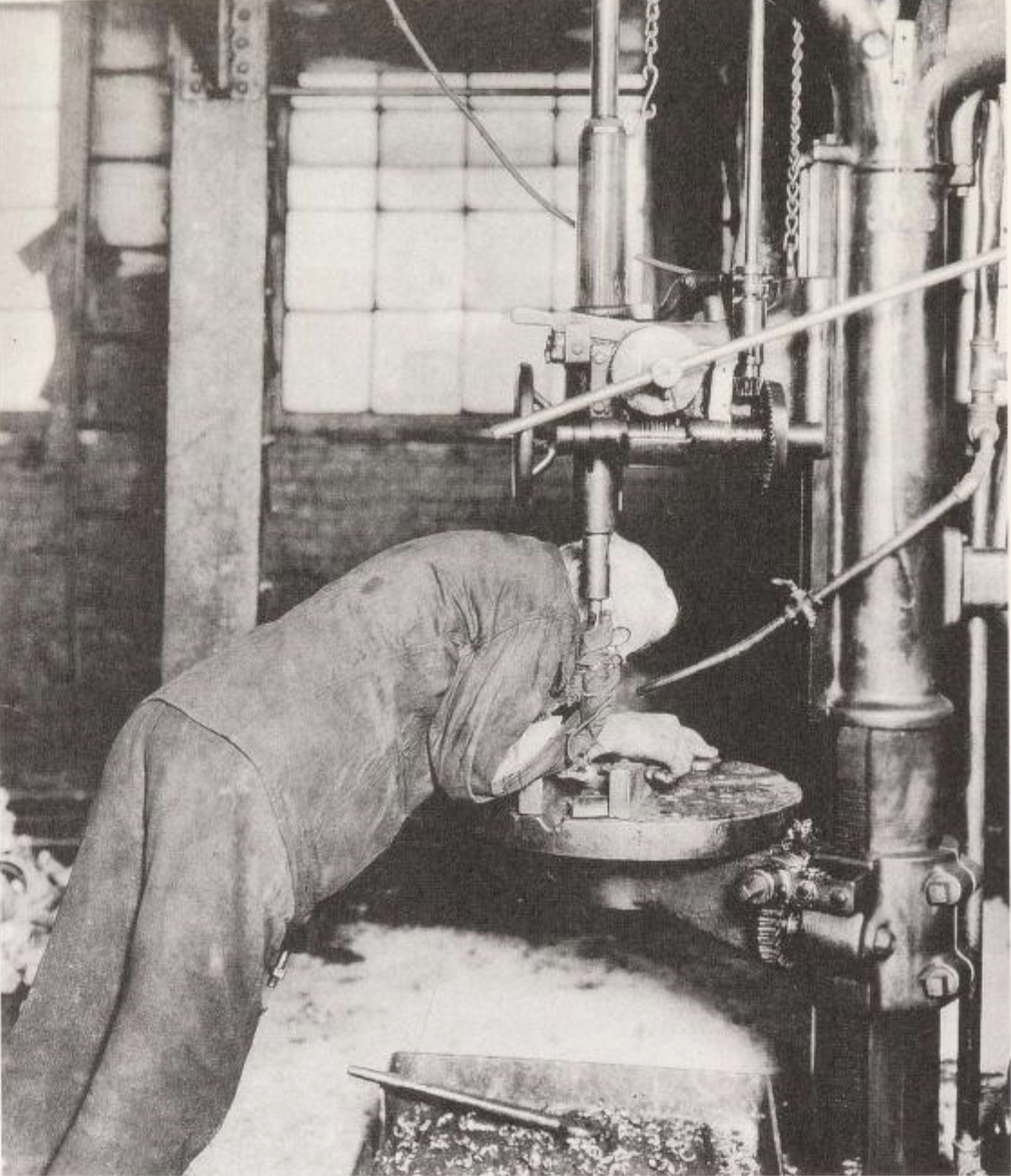

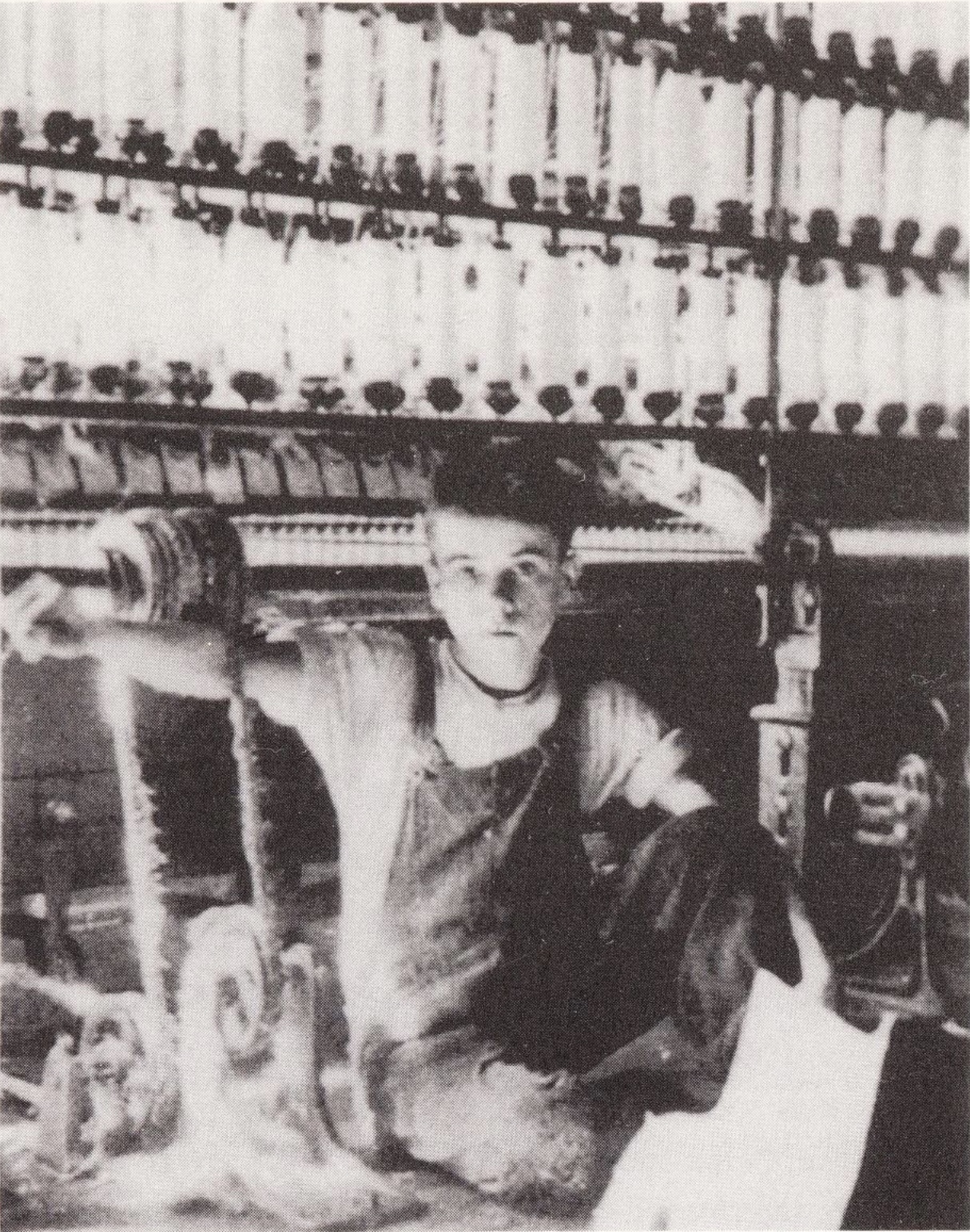

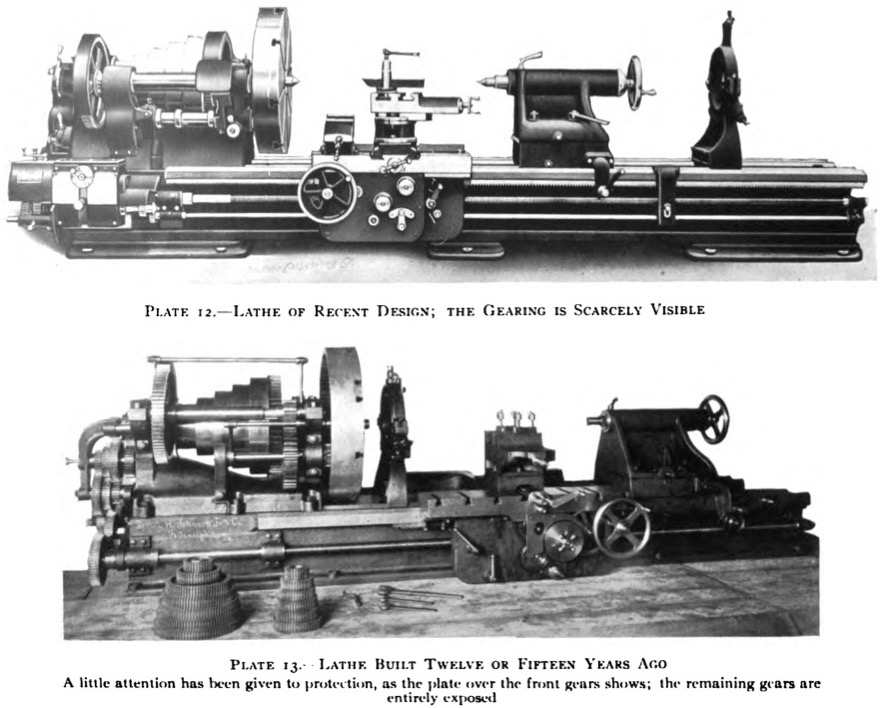

Machines had exposed blades and gears that could catch fingers and hands—woodworking machines, especially joiners, were particularly dangerous. Tools were powered by belts, shafts and flywheels that were similarly unguarded. High above the floor of the factory or mill were walkways and ladders without railings. Cranes could knock workers dead, or drop heavy materials on them. Steam engines had high-pressure boilers, which could explode. High-voltage wires threatened electrocution. Smelting furnaces posed a risk of “hot-metal breakouts”. And workers could be asphyxiated by toxic gases. Workers lost fingers, eyes, limbs, and even their lives to these hazards. (There were also long-term health risks from chemicals, dust inhalation, etc., but for now let’s just consider the risk of accidents.)

The more power was applied, the higher the productivity of the factories, but also the higher the injury rate, as heavier equipment was moving at higher speeds. Safety historian Mark Aldrich writes (p. 165) that in the US from 1869 to 1927, every 1 horsepower per worker was associated with as much as a 3% increase in the injury rate.

There is little in the way of statistics on accidents before the early 1900s, but there is anecdotal evidence that 19th-century factories had higher injury rates than traditional workshops. In 1910, the New York State Compensation Commission wrote that “previous to the introduction of machinery into modern industry, industrial accidents were relatively few and unimportant.” In 1913, Leslie Robertson of the Ford Motor Company said that “the element of injury has been ever present in an increasing ratio as modern development and methods have been utilized” (Aldrich pp 77–78).

What went wrong?

The lack of systems thinking

The root cause of high injury rates was a wrong fundamental attitude towards safety—one shared by both workers and management. Specifically, each individual worker was seen as responsible for his own safety. No one considered it the job of management to provide a safe working environment.

In part, this was a holdover from the previous mode of craft production. Craftsmen were used to managing themselves and taking responsibility for their own safety. This made sense in a shop where workers used hand tools, but not in an industrial factory, where one worker’s actions could endanger others. Fatal accidents happened, for instance, when someone started up a machine not knowing that a repairman was working on it, or when a worker started a car along the rails not realizing that someone was underneath it.

In addition, work was seen as inherently risky. After all, life was inherently risky back then: sailors got lost at sea, poor farmers could starve if struck by drought or blight, and anyone at any time could catch malaria, cholera, or typhoid fever. On-the-job accidents were just part of this general hazardous milieu.

Thus, accidents were typically attributed to worker “carelessness.” Even if partly true, this was a dead end in terms of understanding the causes and how to fix them. It would not survive a modern root-cause or “five whys” analysis. In modern parlance, “systems thinking” was lacking.

Since the contribution of the work environment to safety was not yet acknowledged, accidents were seen as largely unavoidable. Statistical thinking was still in its infancy, and most people had not yet realized how it was possible to exercise agency in the face of rare, random events.

This mentality was reflected in liability laws of the time. It was difficult for accident victims to gain suitable injury compensation from their employers. Their only recourse was a lawsuit—an expensive proposition, then as now. Payments were often small, sometimes covering only funeral expenses, or not even that. And there were multiple ways employers could escape liability. If the worker had been negligent in any way, this was “contributory negligence,” and the employer was off the hook. By the “fellow servant” rule, if one worker’s injury was the result of another worker’s negligence, the employer was again not liable. Finally, by the doctrine of the “assumption of risk,” the employer was not liable if the accident was considered to be within the expected risks of the job. These defenses together were known as the “unholy trinity,” and because of them, it is estimated that only one employee in eight received compensation after bringing suit against their employer.

A new attitude

The late 19th century saw a number of social reform movements aimed at the ills of the factory. There was a movement to end child labor, a movement for shorter hours, and a movement for workplace safety.

In the US, the safety problem was thoroughly explored in a 1910 report Work-Accidents and the Law, by Crystal Eastman (who would go on to become a suffragist and a co-founder of the ACLU). The book-length report was a systematic survey of every fatality and hospitalization in Allegheny County from July 1906 to June 1907. Eastman interviewed workers, foremen, superintendents, and the families of the deceased. She described the accidents themselves, the general risks of the factory, and some of the preventative measures that could be taken. She presented statistics on accidents and their causes. The fundamental conclusion of the report was that in the prevention of accidents, whether directly attributable to the employer or not, “the will of the employer is pre-eminently important.” Work accidents should not be attributed to “carelessness,” but to the lack of safety provisions, inspections, warning systems, and training, and also to the long hours and great speed demanded of the workers.

Eastman’s report was sober and wonkish. Another “muckraker,” William Hard, wrote with more moral force. In a popular article titled “Making Steel and Killing Men,” he asked:

Must we continue to pay this price for the honor of leading the world in the cheap and rapid production of steel and iron? Must we continue to be obliged to think of scorched and scalded human beings whenever we sit on the back platform of an observation car and watch the steel rails rolling out behind us?

Several states set up commissions to study the issue, and they concurred that there was a serious problem. The Illinois commission’s 1910 report (p. 19) declared the present system to be “unjust, haphazard, inadequate and wasteful, the cause of enormous suffering, of much disrespect for law and of a badly distributed burden upon society.”

The reformers proposed a number of different remedies. Hard thought that simply requiring a public report on every accident would go a long way towards effecting change. Some recommended mandating specific safety practices by law, or granting supervisory power to public inspectors. But the key reform turned out to be a fundamental change in the liability law: the creation of “workmen’s compensation.”

Workers’ comp is a “no-fault” system: rather than any attempt at a determination of responsibility, the employer is simply always liable (except in cases of willful misconduct). If an injury occurs on the job, the employer owes the worker a payment based on the injury, according to a fixed schedule. In exchange, the worker no longer has the right to sue for further damages. This reform was enacted first in Germany in 1884 (under Bismarck, who is said to have co-opted it from the socialists in order to defuse their agenda), in Britain in 1897, and state-by-state in the US, mostly during the 1910s.

The new system benefitted both employers and workers. Workers got automatic compensation. Both parties avoided costly lawsuits. Both got a more predictable system and better labor relations. And the system was more efficient, with less money being paid to lawyers and more to accident victims and their families.

The new system, however, dramatically increased employers’ costs. The price to a company of a fatal accident was raised from hundreds to a few thousand dollars, and insurance premiums increased in many cases as much as fivefold. Moreover, the no-fault nature of the system shifted companies’ focus from fighting liability, in the case of lawsuits, to preventing injuries. This shift is exactly what needed to happen. With this new focus and new financial incentive, companies began to set up safety departments, staffed by engineers.

There is a powerful effect to making a goal into someone’s full-time job: it becomes their identity. Safety engineering became its own subdiscipline, and these engineers saw it as their professional duty to reduce injury rates. They bristled at the suggestion that accidents were largely unavoidable, coming to suspect the opposite: that almost all accidents were avoidable, given the right tools, environment, and training.

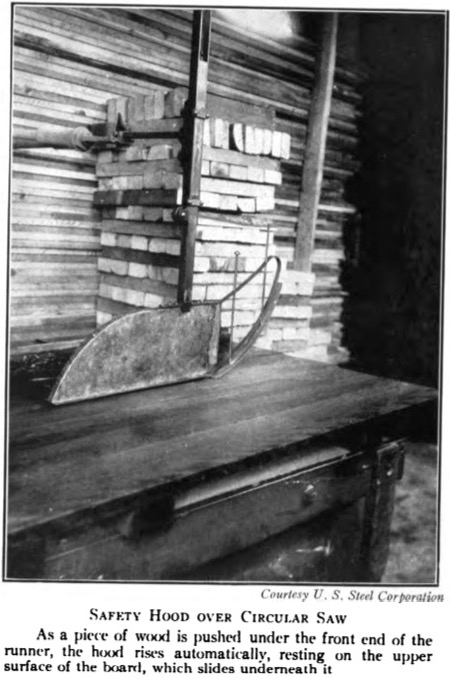

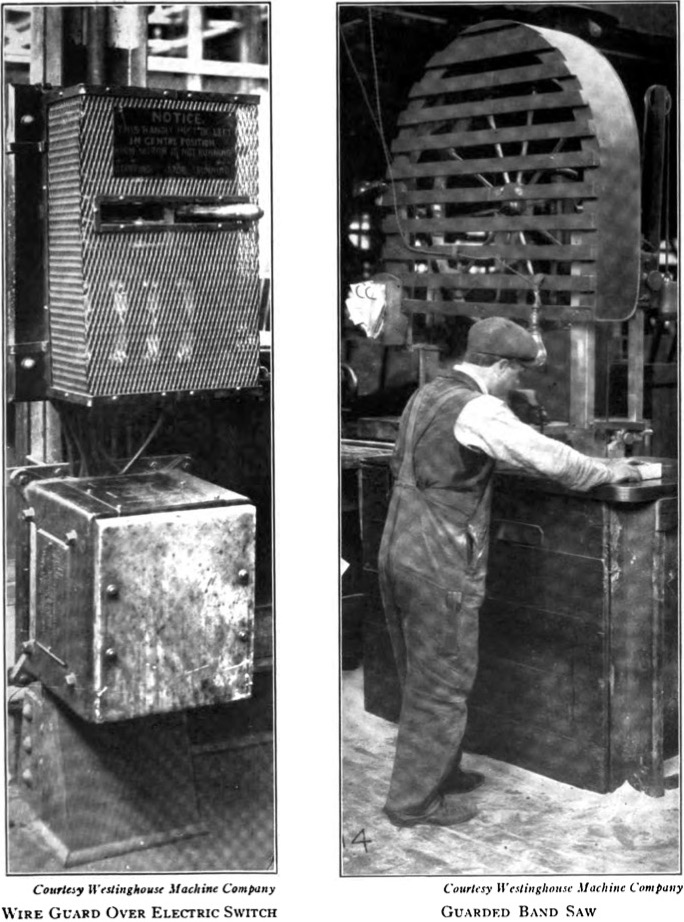

Safety engineering

The new corps of safety engineers began fixing the root causes of injuries. They put guards and enclosures around the moving parts of machines. They invented locks for the machines, so that they couldn’t be turned on unless those guards were in place. They created automatic shutoff mechanisms. They added reversing mechanisms to machines to clear jams, so that workers wouldn’t have to reach in and clear them by hand. They designed power levers that pull outwards instead of in, so that if they are accidentally bumped, the machine turns off, instead of turning on. At the Ford Motor Company, safety engineers made improvements to tools, then shared the blueprints with the toolmakers. In time, a market for safe equipment developed, especially as procurement departments started to give preference to tools with safety features. The machines began to come with guards and enclosures standard; eventually, you couldn’t buy tools without them.

The engineers added railings to walkways and built viaducts for workers to cross tracks (rather than crossing them at grade). They added more clearance around machines and rails. They redesigned and rebuilt blast furnaces stronger, to prevent hot-metal breakouts. They found safer chemicals to substitute for dangerous ones such as ammonia. They designed safety apparel: safety glasses, protective gloves and leggings, hard hats, steel-toed shoes.

Electrification in particular was a boon, not only to safety but to factory working conditions in general. Brighter lighting made it easier to see hazards, and getting rid of candles, oil lamps, and gas light reduced smells, fumes, and the risk of fire. Electric motors eliminated the shafts, belts, pulleys and flywheels that had previously distributed power, all of which could trap arms, clothing and hair. No flywheel also meant that a machine could stop immediately rather than taking time to spin down. And electricity allowed the factory to be completely reorganized: no longer confined to the line of the central power shaft, machines could be arranged to optimize the flow of materials. This minimized handling, which improved both productivity and safety.

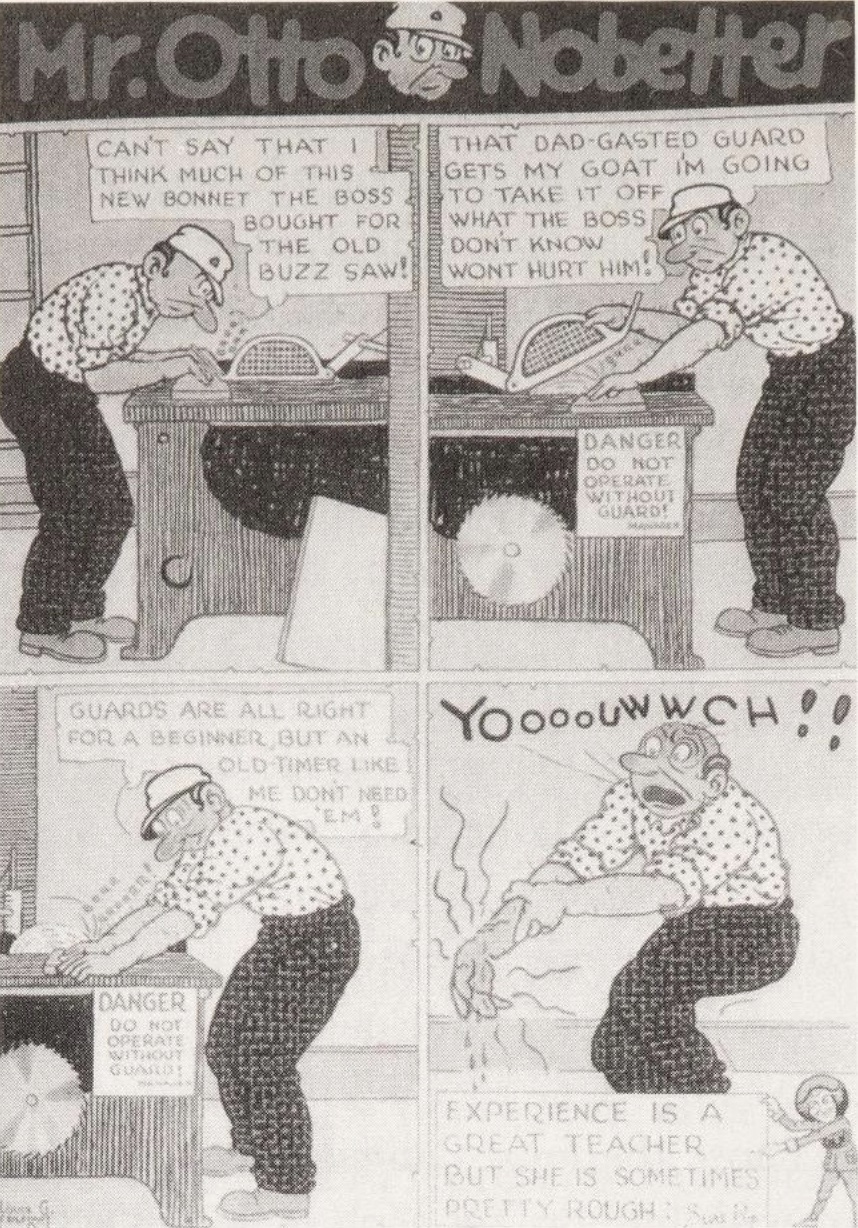

Equally important to these engineering fixes were education and training for the workers. First came simple awareness: you can help prevent accidents. Workers had to be encouraged to use the new safety features of their machines, and not to circumvent them for convenience. Propaganda campaigns were launched, including cartoons featuring the misadventures of characters such as “Willie Everlearn” and “Otto Nobetter.” Safety contests were held, with teams competing for who could reduce injury rates the most. Eventually, as best practices were determined, workers were trained in specific procedures. Aldrich writes (p. 133):

There were safe ways to pile materials, safe places to stand while dressing drive belts, safe methods of placing ladders and of climbing down them, safe methods of lifting, safe ways to sharpen a knife, safe ways to attach a lifting hook, open a fire door, feed a saw, tighten a nut, rig a gangway, lift a load, and move a cart.

Companies also established or upgraded on-site medical care. A factory doctor could attend to injuries right away; this not only sped care, but also kept employees from ignoring minor injuries, or trying to apply ineffective or even harmful self-remedies. Regular checkups also helped: it was discovered that some workers had medical conditions, and should be placed in less physically demanding roles; many others were found to need glasses, and better eyesight improved safety.

Underlying all this was scientific investigation. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics began collecting accident statistics and producing reports. It was observed that accident rates were higher among new employees—one steel company found that employees with less than 30 days experience had accidents at twelve times the company average—which drove home the importance of training for new hires. Injuries were investigated and their root causes determined—no longer would accidents be chalked up to “carelessness.” Line workers were included on the accident investigation committees, to ensure trust and buy-in. The private National Safety Council was created to serve as a clearinghouse of information.

Insurance companies played an important role in all of this. Since they ultimately paid for accidents, they had a strong financial incentive to prevent them and reduce their cost. By serving many clients, they had a broader range of experience than all but the largest manufacturing firms. Some of them specialized in particular industries, which let them determine best practices and encourage or enforce them via factory inspections. They performed their own safety research, published their own pamphlets, and even set up their own medical practices.

All this work paid off: In the early decades of the 1900s, injury rates in many US industries fell dramatically. Data from this period is spotty, but here are figures for injuries per million man-hours from a few different industries, plus the DuPont chemical company (from Aldrich, appendix 3):

| Time period | Start | End | Reduction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steel | 1907 → 1939 | 80.8 | 9.7 | 88% |

| Portland cement | 1909 → 1939 | 97.0 | 4.3 | 96% |

| Paper and pulp | 1920 → 1939 | 46.3 | 15.2 | 67% |

| DuPont | 1912 → 1937 | 43.2 | 1.9 | 96% |

Not all of this reduction is directly attributable to the safety departments; some of it is due to lower turnover and a decline in hours worked per week. Controlling for these factors, however, Aldrich still estimates (p. 164) that safety technology and practices reduced injury rates 3.7%/year from 1926–45, for a total reduction of about 50% over that period.

Safety was led top-down

One striking aspect of the story is that the workers themselves were remarkably unconcerned with safety issues. Safety was led top-down, by management.

Safety did not show up on surveys of US workers’ concerns in the 1800s. Their strikes were almost never motivated by safety issues: in the building and coal trades, across over 50,000 recorded strikes for hundreds of different reasons in the last two decades of the 19th century, there were many thousands over better pay, but only eleven strikes directly due to safety issues. In the coal industry, there were also at least six strikes against safety measures (five to oppose a new safety lamp, and one to allow smoking in the coal mine during lunch). (Aldrich p. 90)

When safety measures were introduced, workers had to be encouraged, trained, coaxed, and propagandized to use them. They often resisted new measures at first. Aldrich writes (p. 136):

The new rules and equipment also represented a loss of workers’ control over their work lives. … “the old-timers disliked being told how to do a job without being hurt. Their idea was that someone had to get hurt, occasionally.” In addition, danger was manly. … “the fellow who wasn’t willing to risk his safety was looked on in modern terms as a sissy.”

Further, the safety movement was led by large companies, not small ones. Some of the first safety programs, even before the new liability laws, were established at big companies like US Steel or DuPont. One reason for this is that large companies were the most visible, and had the most to lose from bad publicity. Another is that they had the resources to invest in safety departments and safety engineering programs. There was also a technical reason having to do with insurance: Large companies would be self-insured against workers’ comp claims; small ones would purchase insurance. However, the insurance premiums sometimes depended only on the company’s industry, giving them no incentive to improve. (This was ultimately addressed by making premiums partly dependent on an employer’s track record, and by giving premium discounts for instituting specific safety measures.)

A lesson I draw from this is that the average person has a hard time thinking about risk. Workers saw the small daily cost—guards and enclosures on machines are inconvenient, hard hats and safety goggles are uncomfortable and unattractive—and weren’t keenly aware of the rare disaster that would be averted. This kind of statistical thinking just doesn’t come naturally to people. (No wonder so many people don’t want to get vaccinated, even against deadly pandemic diseases.)

My conclusion is that safety goals will rarely if ever be driven bottom-up. They are much more likely to be driven top-down, by someone in a position of leadership or authority who sees the statistical picture and can implement the systematic change, including education and training, needed to make it happen.

The unreasonable effectiveness of liability law

I was also impressed with how a simple and effective change to the law set in motion an entire apparatus of management and engineering decisions that resulted in the creation of a new safety culture. It’s a case study of a classic attitude from economics: just put a price on the harm—internalize the externality—and let the market do the rest.

To be clear, part of the reason that so much of the improvement in factory safety can be credited to workers’ compensation is that such regulation as did exist was ineffective. In part, this was due to lack of enforcement support (states typically had fewer than one inspector per thousand shops); in part, manufacturers were often acquitted by juries of their peers. But these very difficulties just highlight the elegance of the liability solution, under which trials were eliminated, and the inspectors were funded by the insurance companies. In any case, it seems to have led to a better outcome than I can imagine being legislated by fiat or micromanaged by regulatory bodies. Aldrich notes (p. 101) that “it proved virtually impossible to write laws that were specific enough to be enforceable and yet flexible enough to fit a broad range of industrial conditions, while technical change often made laws obsolete shortly after they were written.”

Incidentally, Aldrich mentions (p. 132) that:

… the European safety movement had begun with strict requirements for machine guarding, which focused employers’ interests on complying with the law instead of preventing injuries. In the US, on the other hand, the ineffectiveness of early state legislation combined with the spread of workmen’s compensation encouraged businesses to see safety in business terms, not legal terms, and to seek out cost-effective means to prevent injuries.

I don’t yet know whether and how Europe’s outcomes differed from the US. This is an intriguing line for future research.

A related lesson is how much it matters to get the details of the law right. In theory, employers were always liable for injuries. But the old law didn’t give them enough liability, enough of the time, and made it too difficult for workers to seek redress. Workers’ comp dramatically simplified and streamlined the process. In practice, it made the difference between workers getting compensation and not. While it might seem important to make an accurate determination of fault, it turns out that it’s more important to have simplicity, predictability, and low overhead—especially because of the incentives that liability battles put in place. Indeed, I am starting to look with suspicion on any system in which individual workers or consumers have to file a lawsuit to receive compensation.

The system seems so effective that I now wonder where else we could apply similar models. For instance, what if we got rid of medical malpractice lawsuits in favor of a no-fault system in which the medical provider always pays for any complication arising under their care? Maybe this would shift the focus of doctors and hospitals from avoiding liability and following bureaucratic rules, to actually preventing medical accidents in the most effective and efficient manner possible.

Narrative violation?

There is a traditional anti-capitalist narrative of industrial history that goes like this: In the early Industrial Revolution, greedy capitalists who put profits over people exploited powerless workers—even women and children—by making them work long hours at arduous jobs in dim, dirty, smelly, dangerous factories. Callous and heartless, they squeezed every penny of profit out of the helpless workers. Then, heroic social reformers came along and brought the capitalists to heel, empowering the worker and rescuing them from their plight. Reformers gave workers the 40-hour week, eliminated child labor, and brought safety and hygiene to factories.

Another narrative might go like this: Actually, the historical progression was natural and inevitable. Shorter hours, cleaner and safer factories, and the end of child labor are luxuries that could only happen after an increase in per-capita wealth. These things go through a kind of Kuznets curve, naturally getting worse in the early stages of economic growth, then getting better later. The factory system, including its harsh discipline, was needed to pull the pre-industrial world out of the poverty it had been mired in for millenia. In this telling, there’s no way the problems could have been avoided in the early period—and their solution was natural and inevitable in the later period. It was economic progress itself, not muckrakers and labor unions, that solved them.

Which narrative, if either, is bolstered by the story of factory safety? Let’s explore this through a dialogue between Paul the Progressive and Carla the Capitalist:

P: The history of workplace injuries shows the evil of capitalism and the need for progressive reform.

C: No, it shows no such thing!

P: Capitalist factories had very high injury rates, and management didn’t care. It was only after progressive reformers called attention to the problem and got the law changed that things improved!

C: No, the dangerous factory environment was the result of attitudes left over from the previous age. Workers themselves were unconcerned for their own safety—they often resisted safety measures, and even struck against them! And no one knew exactly what safety measures were needed, anyway—that required a process of investigation and engineering. The whole thing was a natural progression of error and learning, made possible by surplus wealth. Safety is a luxury that we purchased once we were rich enough.

P: Sure, some learning was needed—but it could have happened faster. US factories were still highly dangerous in 1910, many decades into the Industrial Revolution, and decades after liability reform had already happened in Europe. There were obvious safety measures that could have been taken, and weren’t. Management could have put resources into this, but didn’t—until it hurt their pocketbooks. They just didn’t care about the workers.

C: Were the safety measures really obvious? They look that way in retrospect, but it’s always obvious after an accident happens; it’s much harder to tell, with finite resources, what preventative measures you should take. And your theory that management didn’t care doesn’t fit with the fact that it was actually the biggest companies who led the way in safety. Are you trying to tell me that big bureaucracies care more about their workers on a personal level than small shops?

P: Fine. There’s no need to get personal and blame “heartless management”. This isn’t the moral failing of any individual, but of a system. Even if it wasn’t obvious which specific safety measures to take, it should have been obvious that the factory was too dangerous—that much was clear to the public once the reformers put a spotlight on the issues.

C: Sure, but some danger is inherent in work, and the world was a dangerous place in the 19th century. Capitalism didn’t invent danger—mining and logging were plenty dangerous well before the Industrial Revolution. Besides, ultimately, businesses respond to incentives. The law tells them their responsibilities, and they don’t have an obligation to go above and beyond that. In fact, if they do, they might fail in competition to those who are more efficient.

P: I agree: businesses respond to incentives, and they do only the bare minimum the law requires, no more! That is exactly my point: capitalism gives them powerful and dangerous incentives, which increase real wages, but at a terrible and deadly cost. That’s exactly why corporations need to be reined in by laws that protect workers.

C: Well, I agree that capitalism rests on a legal foundation that includes protecting people’s rights! What we had here was a case where the law failed, in practice, to protect the right not to be injured through the negligence of others. That’s why legal reform was needed. The problem here wasn’t capitalism, it was the inadequate protection for certain rights—human rights that apply to everyone, not special “workers’ rights.”

P: It’s fine for you to say that now, with the benefit of hindsight. But it was all too easy, back then, for people to defend the status quo by saying that workers’ rights were protected, by the existing liability laws. It was easy to argue against workers’ comp on the grounds that not all injuries were the employer’s fault. And it was easy to claim that employers and workers had agreed to a job with known risks, and that it’s not the place of the law to tell people what risks they should be willing to accept for what reward. So even if you can frame this as a simple issue of liability in retrospect, the reform would never have happened except for people who cared deeply for something they call “workers’ rights.”

C: You’re right about how easy it was to defend the status quo on seemingly reasonable grounds. But that doesn’t mean we have to start viewing the world through the lens of class warfare. This was simply a case where systems thinking was required, to understand that accidents should be attributed to the work environment rather than to individual “carelessness.” And where the mechanism of the law needed to be streamlined, to avoid costly lawsuits.

P: Maybe… but employers also argued that workers had accepted the risks of the job. Under your laissez-faire principles, the worker has the “right” to sign a contract in which he assumes any level of risk. Indeed, this was known at the time as the “right to die!”

C: No, you can’t sign away all your rights. You can’t sell yourself into slavery, for instance. Perhaps on a similar principle, you can’t agree to waive all compensation for injury.

P: Great, I’ll see you and raise you: you can’t agree to waive your right to a living wage, shorter hours, etc.… apparently the whole progressive agenda can be built on your laissez-faire foundation!

C: No, now you’re not talking about injury, but benefits. You’ve flipped from negative rights, the right not to be injured, to so-called “positive rights”, such as pay and convenient hours. I still say those issues should be decided on the free market, not through intrusive, paternalistic government regulation.

P: Well, I’d love to debate you on that point, but let’s stay focused on safety for now. I’ll agree that some initial rise in accident rate might have been inevitable in the transition to a new mode of production. But the safety movement was not inevitable—it was the result of progressive reformers. Capitalism would never have accomplished this on its own.

C: Well… I have to admit, reformers like Eastman and Hard seem instrumental in this story. Their work helped bring about the legal reform, and the legal reform brought about the safety departments. So, I have to give them credit for that.

P: Good.

C: Honestly, I just bristle at most muckrakers because they’re so hostile to business—you know, the caricature they paint of the evil greedy heartless capitalist. Still, if we’re being intellectually honest, we have to face the brutal reality of the problems that progress has created, even as we remain optimistic about our ability to solve them with more progress—the “solutionist” mentality. And that means I should at least listen to the reformers, because they might be pointing out a real problem—even if I have to disentangle it from a worldview that I reject.

P: Well, I’d love to debate you on the “muckrakers”—but then we’d be here all day!

Sources and further reading

Most of the historical narrative here is based on Chapters 3–4 of Safety First, by Mark Aldrich, an economist and former OSHA investigator. Aldrich also wrote an entry for the EH.net encyclopedia, “History of Workplace Safety in the United States, 1880-1970.”

The story of Angelo, and the historical statistics in the introduction, are from Chapter 4 of Work-Accidents and the Law, the 1910 exposé by Crystal Eastman. (A note at the beginning of the book indicates that the names of workers are fictitious.)

“Making Steel and Killing Men”, by William Hard, was reprinted along with other relevant articles in Injured in the Course of Duty, also published in 1910.

Report of the Employers’ liability commission of the state of Illinois, 1910.

The Safety Movement in the Iron and Steel Industry 1907 to 1917, a report by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

National Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries in 2019, Bureau of Labor Statistics, summary news release.

Industrial accidents—worker compensation laws and the medical response, J S Haller Jr, Western Journal of Medicine, 1988.

A Brief History of Worker’s Compensation, Gregory P Guyton, Iowa Orthopedic Journal, 1999.

William Hard as Progressive Journalist, Ron Marmarelli, American Journalism, 1986.

Crystal Eastman (Wikipedia).