The American Information Revolution in Global Perspective

Reflections on Robert Allen's explanation for the Industrial Revolution

by Jason Crawford · May 26, 2023 · 5 min read

In “What if they gave an Industrial Revolution and nobody came?” I reviewed The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective, by Robert Allen. In brief, Allen’s explanation for the Industrial Revolution is that Britain had high wages and cheap energy, which meant it was cheaper to run machines than to pay humans, and therefore it was profitable to industrialize. He emphasizes these factors, the “demand” for innovation, over explanations based in culture or even human capital, which provide “supply.”

While I learned a lot from Allen’s book, his explanation doesn’t sit right with me. Here are some thoughts on why.

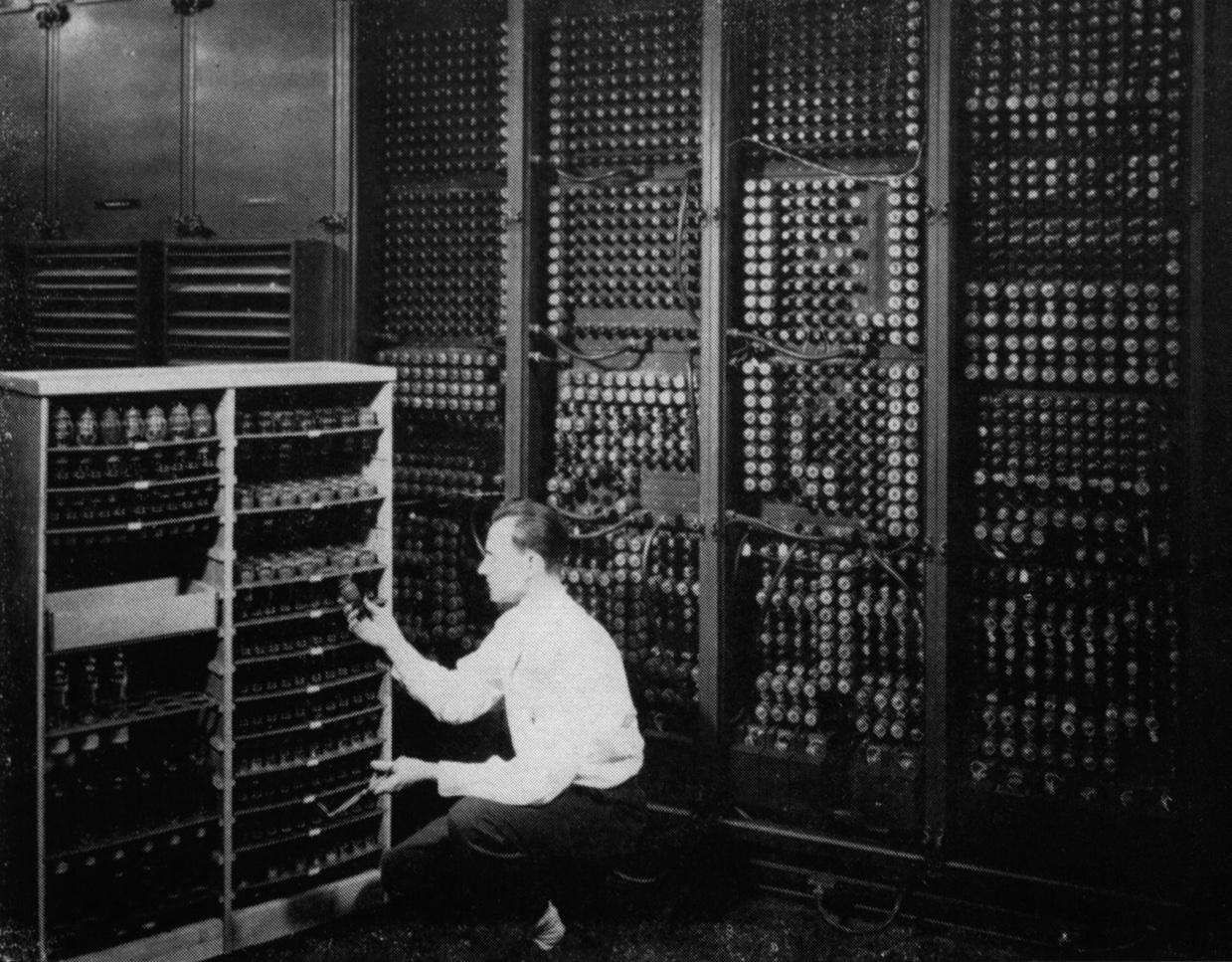

Suppose you took Allen’s demand-factor approach to explain, not the 18th-century Industrial Revolution in Britain, but the 20th-century Information Revolution in America. Instead of asking why the steam engine was invented in Britain, you might ask why the computer was invented in the US.

Maybe you would find that the US had high wages, including for the women who acted as human computers by performing arithmetic using mechanical calculators; that it had cheap electricity, owing to early investments in generation and the power grid such as large hydroelectric power plants at Niagara and the Hoover Dam; that it had a plentiful supply of vacuum tubes from the earlier development of the electronics industry; and that there was an intense demand for calculation from the military during WW2.

Maybe if you extended the analysis further back, you would conclude that the vacuum tube amplifier was motivated in turn by solving problems in radio and in long-distance telephony, and that demand for these came from the geography of the US, which was spread out over a large area, giving it more need for long-distance communications and higher costs of sending information by post.

And if you were feeling testy, you might argue that these factors fully explain why the computer, and the broader Information Revolution, were American—and therefore that we don’t need any notion of “entrepreneurial virtues,” a “culture of invention,” or any other form of American exceptionalism.

Now, an explanation like this is not wrong. All of these factors would be real and make sense (supposing that the research bears them out—all of the above is made up). And this kind of analysis can contribute to our understanding.

But if you really want to understand why 20th-century information technology was pioneered by Americans, this explanation is lacking.

First, it’s missing a lot of context. Information technology was not the only frontier of progress in America in the mid-20th century. The US led the world in manufacturing at the time. It led the oil industry. It was developing hybrid corn, a huge breeding success that greatly increased crop yields. Americans had invented the airplane, and led the auto industry. Americans had invented plastic, from Bakelite to nylon. Etc.

And to start with the computer is to begin in the middle of the story. The US had emerged as the leader in technology and industry much earlier, by the late 1800s. If it had cheaper electricity, that’s because electric power was invented there. If it had IBM, a large company that was well-positioned to build electronic business machines, that’s because it was already a world leader in mechanical business machines, since the late 1800s. If it had high wages, that was due to general economic development that had happened in prior decades.

And this explanation ignores the cultural observations of contemporaries, who clearly saw something unique about America—even Stalin, who praised “American efficiency” as an “indomitable force which neither knows nor recognizes obstacles… and without which serious constructive work is inconceivable.”

I think that the above is enough to justify some notion of American exceptionalism. And similarly, I think the broader context of European progress in general and British progress in particular in the 18th century justify the idea that there was something special about the Enlightenment too.

Here’s another take.

Clearly for innovation to happen, there must both supply and demand. Which factors you emphasize says something about which ones you think are always there in the background, vs. which ones are rate-limiting.

By emphasizing demand, Allen seems to be saying that demand is the limiting factor, and by implication, that supply is always ready. If there is demand for steam engines or spinning jennies, if those things would be profitable to invent and use, then someone will invent them. Wherever there is demand, the supply will come.

Emphasizing supply implies the opposite: that supply is the limiting factor. In this view, there is always demand for something. If wages are high and energy is cheap, maybe there is demand for steam engines. If not, maybe there is demand for improvements to agriculture, or navigation, or printing. What is often lacking is supply: people who are ready, willing and able to invent; the capital to fund R&D; a society that encourages or at least allows innovation. If the supply of innovation is there, then it will go out and discover the demand.

This echoes a broader debate within economics itself over supply and demand factors in the economy. Allen’s explanation represents a sort of Keynesian approach, focused on demand; Mokyr’s (or McCloskey’s) explanation would imply a more Hayekian approach: create (cultural and political) freedom for the innovators and let them find the best problems to solve.

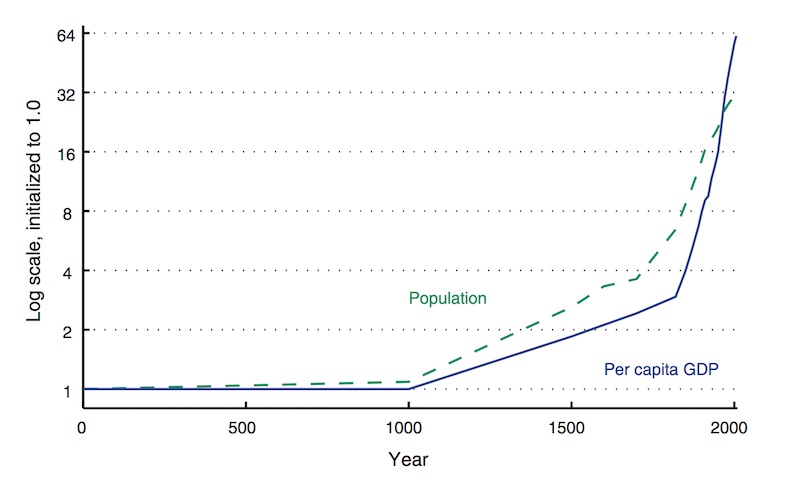

Part of why I lean towards Mokyr is that I think there is always demand for something. There are always problems to solve. Allen aims to explain why a few specific inventions were created, and he finds the demand factors that created the specific problems and opportunities they addressed. But this is over-focusing on one narrow phase of overall technological and economic progress. Instead we should step back and ask, what explains the pace of progress over the course of human history? Why was progress relatively slow for thousands of years? Why did it speed up in recent centuries?

It can’t be that progress was slow in the ancient and medieval world because there weren’t many important economic problems to solve. On the contrary, there was low-hanging fruit everywhere. If the mere availability of problems was the limiting factor on progress, then progress should have been fastest in the hunter-gatherer days, when everything needed to be solved, and it should have been slowing down ever since then. Instead, we find the opposite: over the very long term, progress gets faster the more of it we make. Progress compounds. This is exactly what you would expect if supply, rather than demand, were the limiting factor.

Finally, I have an objection on a deeper, philosophic level.

If you hold that an innovative spirit has no causal influence on technological progress and economic growth, then you’re saying that people’s actions are not influenced by their ideas about what kinds of actions are good. This is a materialist view, in which only economic forces matter.

And since people do talk a lot about what they ought to do, since they talk about whether progress is good and whether we should celebrate industrial achievement, then you have to hold that all of that is just fluff, idle talk, blather that people indulge in, an epiphenomenon on top of the real driver of events, which is purely economic.

If you adopt an extreme version of Allen’s demand explanation (which, granted, maybe Allen himself would not do), then you deny that humanity possesses either agency or self-knowledge. You deny agency, because it is no longer a vision, ideal, or strategy that is driving us to success—not the Baconian program, not bourgeois values, not the endless frontier. It is not that progress came about because we resolved to bring it about. Rather, progress is caused by blind economic forces, such as the random luck of geography and geology.

And further, since we think that our ideas and ideals matter, since we study and debate and argue and even go to war over them, then you must hold that we lack self-knowledge: we are deluded, thinking that our philosophy matters at all, when in fact we are simply following the path of steepest descent in the space of economic possibilities.

I think this is why the Allen–Mokyr debate sometimes has the flavor of something philosophical, even ideological, rather than purely about academic economics. For my part, I believe too deeply in human agency to accept that we are just riding the current, rather than actively surveying the horizon and charting our course.

Relevant books

The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective